Auctions

Led by a Sizzling Bacon, Sotheby’s First-Ever Hybrid Contemporary Evening Sale Format Nets an Impressive $300.4 Million

The carefully choreographed sale took place on three continents.

The carefully choreographed sale took place on three continents.

If a time traveler from 2019 arrived at Sotheby’s evening sale on Monday evening, she would have been very confused by what she saw. There was no packed salesroom, no paddles, no air kissing. Instead, specialists were stationed six feet apart on tiered rows of phone banks and the entire production was livestreamed simultaneously from Hong Kong, London, and New York. The auction marked the first major test of the art-market’s upper echelons during the social-distancing era—and it would be fair to say the house passed.

In all, the marathon evening generated a total of $363.2 million and consisted of three parts: a single-owner sale of works assembled by the late cable television mogul Ginny Williams; postwar and contemporary selections; and an Impressionist and Modern art coda. (More on that final chapter here.)

In total, Sotheby’s postwar and contemporary art offerings made $300.4 million: $65.5 million for the Williams collection and $234.9 million for the main PWC sale, which came in on the high end of the presale estimate range of $171.4 million to $239.1 million. (Final prices include the buyers’ premium; estimates do not.)

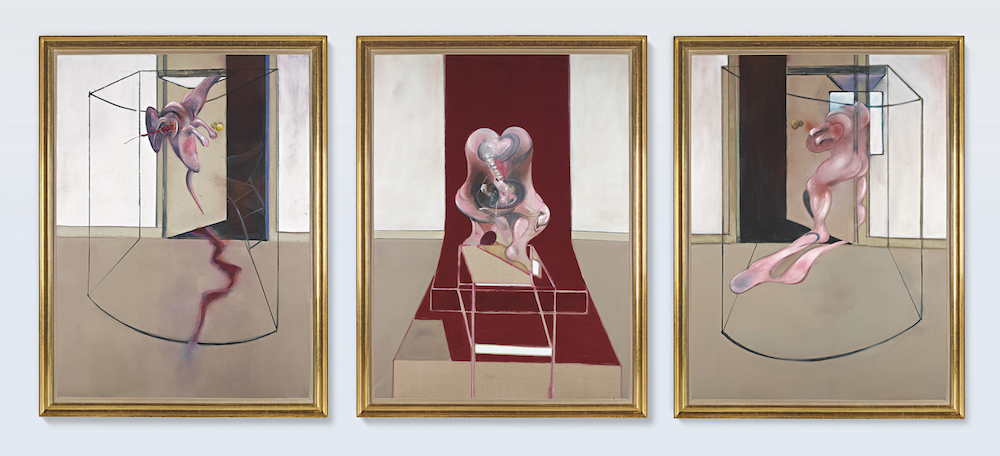

The most expensive lot of the night was Francis Bacon’s Triptych Inspired by the Oresteia of Aeschylus (1981), which fetched $84.6 million with fees, just over the pre-sale high estimate of $80 million. It was offered by a foundation tied to Norwegian billionaire Hans Rasmus Astrup.

Francis Bacon, Triptych Inspired by the Oresteia of Aeschylus (DATE). Image courtesy of Sotheby’s

The postwar and contemporary chapter, including the Williams sale—which saw only one lot fail to find a buyer—were a testament to the unflappability of the top end of the market, even in an uncertain moment. (The record for the most expensive work ever sold to an online bidder was broken twice.) But the event was also carefully choreographed; many of the works carried guarantees, making them certain to sell.

Expectations were high going in. “I think they have a lot of people’s attention,” said art advisor Lisa Schiff told Artnet News ahead of the sale. “This is the first big, concentrated, select group of things at a public auction.”

The new format also lasted far longer than anyone could have anticipated: kicking off at 6:30 p.m. in New York, it stretched on four-and-a-half hours, leaving auction staff bleary-eyed (particularly in London, where the proceedings concluded at the ripe hour of 4 a.m.).

Joan Mitchell, Straw (1976). Image courtesy Sotheby’s.

The sale kicked off with 18 works from the Ginny Williams collection, assembled by the late Denver philanthropist who made a fortune in the cable-television industry with her husband, Carl Williams. Ginny, who died last fall at the age of 92, was known for her vibrant personality and her interest in the work of female artists.

As dealer Nicholas Maclean noted ahead of the sale, the holdings were fresh to market and fairly priced, which is “what the market wants when there’s a little uncertainty.” The collection was also directly guaranteed by the house, so, not surprisingly, all 18 lots on offer were sold. (Sotheby’s also offloaded the risk on a few objects via last-minute third-party guarantees.) All told, the Williams works realized $65.5 million, healthily surpassing the pre-sale estimate of $35.9 million to $51.7 million.

The first lot to catch fire was Royal Fireworks (1975), a burnt orange canvas that carried an estimate of $2 million to $3 million. After auctioneer Oliver Barker opened the bidding at $1.6 million, the work was immediately chased by Sotheby’s specialists Amy Cappellazzo and Brooke Lampley, ultimately going to Lampley’s client for $7.9 million with fees, and more than doubling artist’s previous auction record of $3 million.

Helen Frankenthaler, Royal Fireworks (1975). Image courtesy Sotheby’s.

Abstract Expressionist painter Joan Mitchell—whose top four prices at auction have all been set within the past two years—was also a star of the Williams collection, with three major works on offer. The priciest, Straw (1976), was estimated at $5 million to $7 million and was chased by three Sotheby’s specialists before it was hammered down, to a very busy Lampley, for $5.5 million, or $8.8 million with premium.

“Even though the prices for Joan Mitchell have gone up so much in the past two years,” Schiff said ahead of the sale, “she is one of the best Abstract Expressionist painters ever and she is so far behind the men. In a nanosecond, you will not be able to buy anything by her.”

Also of note was a record for the Latvian American artist Vija Celmins, who works slowly and whose paintings relatively rarely hit the auction block. Night Sky #7 (1995) sold for $6.6 million, surpassing the artist’s previous record of $4.2 million set in November 2017.

Not surprisingly, the heavyweight eight-figure works came in the main contemporary section, though the underlying bidding activity did not always line up with the actual result.

Weighing in on the offerings, Maclean said that “the main evening sale is for the most part well-priced and predictable… we needed them to be responsible and they have been.”

The megawatt lot, a major Bacon’s triptych, opened for bidding at $48 million. As it made its way up to $60 million, an extremely odd pattern began to emerge. A bid placed by Grégoire Billault, head of the contemporary art department, was suddenly bested by a mysterious online bidder from China who raised the price by $100,000—an extremely small increment considering the hefty price.

Billault’s bidder then leapt a full $900,000 further, to $61 million. The cat-and-mouse bidding war carried on, with tiny increments battling large ones, for a total of $14 million, until Billault’s big-bidding client finally grasped the prize. (The work is now the third most expensive Francis Bacon ever sold at auction, well behind Three Studies of Lucian Freud, which sold for $142.4 million at one of the market’s recent peaks in 2013.)

Matthew Wong, The Realm of Appearances (2018). Photo: Sotheby’s.

Another eye-watering market moment came at the start of the contemporary sale, when a work by Matthew Wong, a rising art star who died by suicide last fall at the age of 35, kicked off the sale. The Realm of Appearances (2018), a brilliantly colored forest scene purchased by a flipper from Wong’s first show at Karma Gallery in 2018, was estimated at $60,000 to $80,000.

Considering that the artist’s work is essentially impossible to get on the primary market, competition was unsurprisingly furious. After bids from specialists in Hong Kong, it ultimately hammered down to Lampley’s client for $1.5 million, or $1.8 million with premium. The previous auction record for the artist was $62,500 for a work on paper sold in a Sotheby’s online sale last month.

Another moment of heated competition came when Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Untitled (Head) (1982), which carried an estimate of $9 million to $12 million (as well as a third-party guarantee), hit the block, ultimately selling for $15.2 million. It marked the highest price ever paid at Sotheby’s by an online bidder, surpassing the $7.9 million spent for one of the Williams collection’s Mitchells earlier in the evening.

The Basquiat was last offered at Phillips New York nearly 20 years ago, in 2000, where it sold for $398,500—marking a hefty 3,714 percent increase upon its return to auction.