The Art Detective is a weekly column by Katya Kazakina for Artnet News Pro that lifts the curtain on what’s really going on in the art market.

Art fairs have survived months of lockdowns, cancellations, drastically reduced bottom lines, and belt-tightening. Now comes the next hurdle: Brain drain.

Several prominent executives at major trade shows including Art Basel, Frieze, and the Armory Show have decamped this year, adding to growing concerns about the future of the business model.

“No one believes it’s sustainable,” said Alain Servais, a Brussels-based collector and industry observer. “If you are a manager or executive with a little bit of ambition, you understand that it’s not the place to stay.”

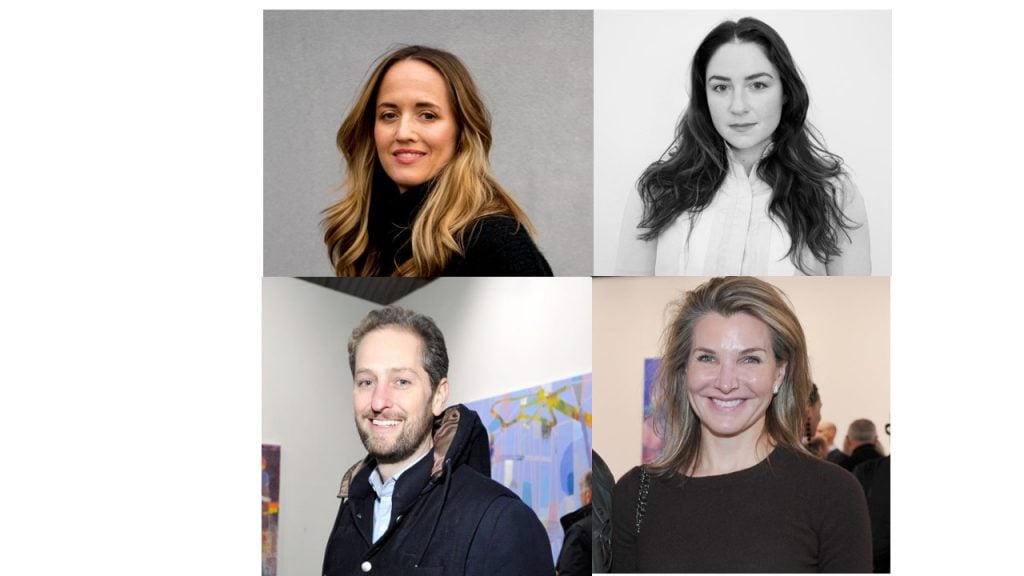

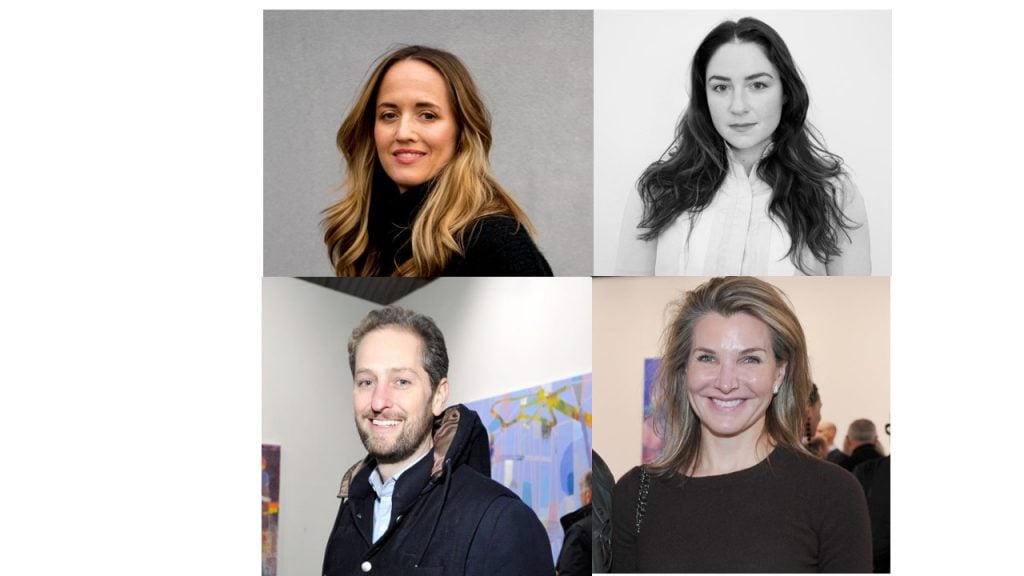

Noah Horowitz, who had been director of Art Basel in the Americas since 2015 and was believed to be next in line to lead the company, joined Sotheby’s last month to develop its services for galleries and private dealers. Eliza Osborne, deputy director of the Armory Show in New York, quit days after the fair concluded its first edition since the pandemic in September. Rebecca Ann Siegel, director of Frieze Americas, stepped down in August after one year in the role. Her predecessor, Loring Randolph, moved on to become director of the Nancy A. Nasher and David J. Haemisegger Collection in Texas.

From left: Loring Randolph, Rebecca Ann Siegel, Noah Horowitz, and Eliza Osborne.

The pandemic hit art fairs particularly hard as live events were canceled and international travel came to a screeching halt. Without booth-rental income, revenues plummeted. Online viewing rooms, a key innovation of the Covid era, were mostly offered for free, especially early on, and didn’t add much to the bottom line (to the chagrin of the fairs’ corporate owners).

At the same time, galleries, which had come to rely on art fairs for much of their sales, realized that they could survive without them. (This was particularly notable considering that art-fair sales accounted for around 48 percent of dealer revenue in 2019, according to the Art Basel UBS Art Market report.) Sure, income was down—but so were expenses. In the end, just a few galleries were forced to close and many found new ways to thrive and grow.

Instead, it’s the art-fair industry that is facing a reckoning.

The problems were already there, one industry insider told me: “The pandemic just put a mirror up to everybody’s face.”

When Covid-19 hit, most major cities had an art fair, some more than one. A recent pre-pandemic count estimated these events numbered over 300—one for almost every day of the year.

“People were exhausted from the number of fairs, the treadmill that the art world has become,” said Paul Morris, a cofounder of the Armory Show, who left in 2012. “Maybe it’s time to reassess things, to get some balance. Or maybe we’ll just go back because there was so much money and success involved.”

The Armory Show 2021 at the Javits K. Jacob Convention Center in Manhattan on September 10, 2021. Photo by Tayfun Coskun/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images.

Collectors aren’t the only people questioning the model’s sustainability. “Outsiders looking at people who work for fairs see a glamorous lifestyle,” said Sue Hostetler Wrigley, a longtime editor-in-chief of Art Basel Magazine, who stepped down in 2020 to co-found Hostetler/Wrigley Foundation. “But it’s grueling. They are all over the world all the time. It’s even harder for mothers. And it doesn’t stop. There’s a tremendous burnout.”

Change may be already afoot as power dynamics between exhibitors and fair organizers have shifted. A few years ago, galleries were clamoring to get into the fairs, Servais said over the phone from Paris’s FIAC, his fourth trade event in one month.

Now they are clamoring for discounts—and the fairs are doing whatever they can to ensure galleries don’t pull out.

Art Basel slashed prices for its marquee Swiss fair by 10 percent in the spring and then, under mounting pressure from exhibitors, pulled together a $1.6 million “Solidarity Fund” to help reduce costs further in the eleventh hour. (Organizers have yet to reveal the number of galleries that chose to take advantage of the relief.) At this year’s Frieze New York, dealers ended up paying less for booths than they had in previous years because the stands at its new venue, the Shed, were smaller. Meanwhile, Art Cologne, which returns next month, will refund its exhibitors 34 percent thanks to funding from the German government.

These are temporary solutions, of course. Long-term, said Marc Spiegler, global director of Art Basel, “it’s important we continue to leverage two things that arose during the pandemic: one being the new digital tools and innovations that we and our galleries developed; and the other the strong sense of collegiality.”

Art Basel 2021. © Art Basel

Many of the top fairs, including Art Basel and the Armory Show, were founded by art dealers. But as the industry grew, the trade shows proliferated and expanded, attracting corporate backers as key sponsors as well as outright owners. The Armory Show is now owned by a real estate conglomerate, Vornado. Entertainment company Endeavor acquired a 70 percent stake in Frieze in 2019. Art Basel’s owner, the MCH Group, attracted a new investor over the summer, James Murdoch.

“If you are now owned by a multi-national corporation, you have a lot of other agendas to meet that are purely financial,” said Elizabeth Dee, cofounder of the Independent art fair in New York. “Those are businesses and there’s a lot of pressure to make money.”

One challenge is to expand beyond being once-a-year mega production (like a wedding) in order to spread out fixed costs (like salaries).

Dee, for her part, is leaning into digital content for original programming—including editorial, podcasts, and roundtable discussions—during the off season. “There’s such an opportunity for the next generation to come in and say: I want to go beyond fairs,” she said. “You need to create connections between dynamic, powerful storytelling online and dynamic, powerful exhibitions at the fair. The great future fairs have to believe that these two things [are] equal.”

Pop-up events in wealthy enclaves may be another strategy. “Like Frieze in the Hamptons,” said Servais. “People will come.”

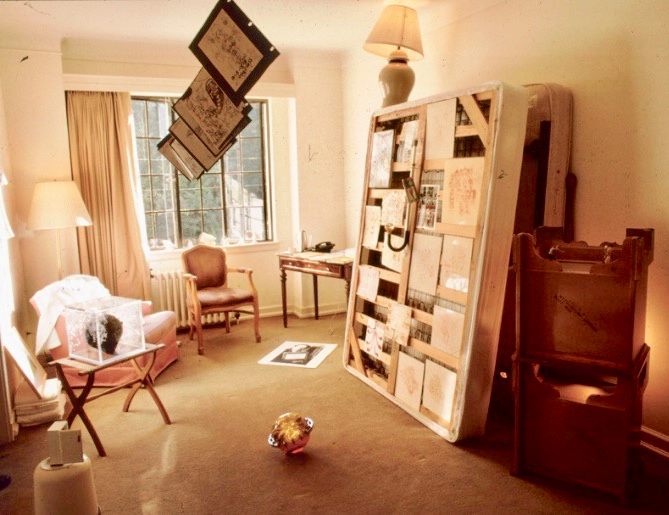

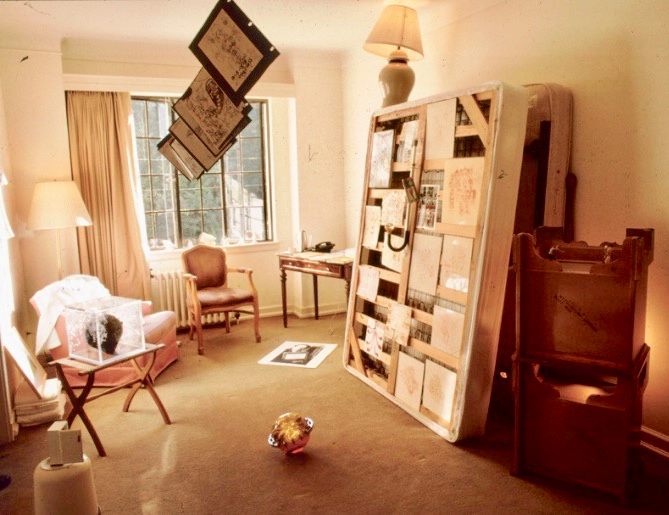

Where it began, the proto-Armory Show known as the Gramercy International Art Fair in the mid-’90s, here with an installation by Rachel Harrison. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Some of the best ideas, events, and shows have come out of adversity, Morris said. In 1994, when the art world was in the middle of a downturn, he joined three other dealers to launch an art fair at the Gramercy Park Hotel, charging galleries $50 for a room.

The event would later become known as the Armory Show, expanding to a flurry of events and satellite fairs known as Armory Week.

“The art world is really open to new ideas,” he said. “Now art fairs have a chance to look at how they are operating and find a balance between being in-person and online. Basel programs the whole city with events and people like to see all that. But if you can’t make it, it doesn’t mean you can’t buy.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.