It feels like déjà vu. The art world’s most closely watched collection of postwar treasures, amassed over decades by Linda and Harry Macklowe, is inching toward the auction block. Again.

The couple’s acrimonious split has fueled gossip columns and tantalized art sellers ever since Linda Macklowe filed for divorce from her billionaire real-estate developer husband five years ago. At stake is their trove of prized Picassos, Warhols, and Twomblys, which has been estimated to be worth more than $700 million. A court ordered dozens of works to be sold at auction after the warring spouses were unable to agree on valuations for their priciest pieces. A judge brought in an outside expert to oversee the dispersal on a three-year deadline.

Following many months of anticipation, top works from the collection are now expected to hit the auction block in November, according to people familiar with the matter who asked not to be named because the court hadn’t given its rubber stamp yet. (Sources also cautioned that further legal or public health challenges could push that date back further.) Of the 165 works in the couple’s holdings, 64 will be sold, with an estimated value of $625.6 million to $788.7 million.

The sale will be the biggest test of the 20th century masterpiece market since the pandemic struck. Supply has been scarce in this top tier, with sellers reluctant to consign major works to auction in a moment of global uncertainty. Billionaire Ron Perelman sold much of his prized art privately last year, generating about $500 million.

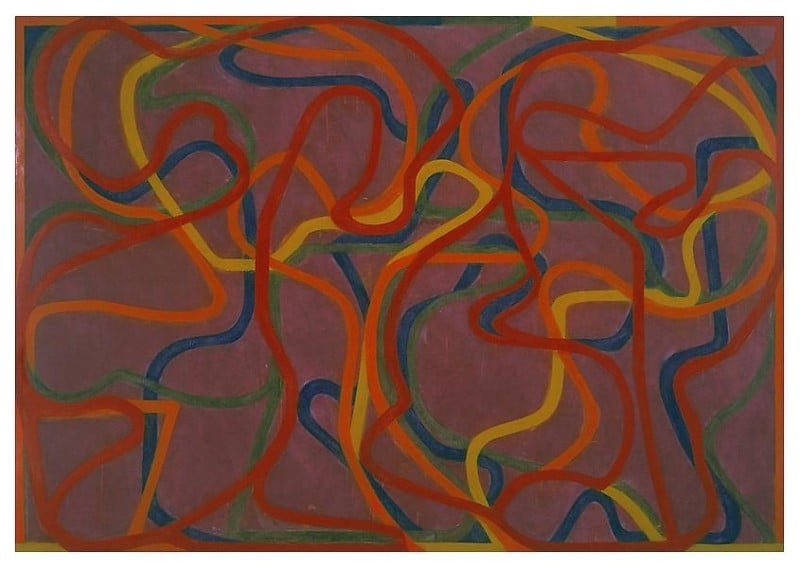

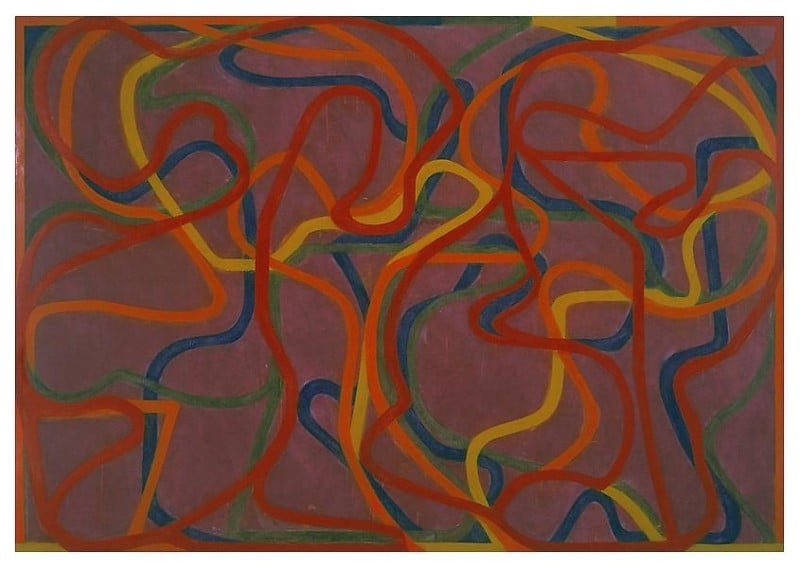

Brice Marden, Red Rocks (5) (2000–2). Brice Marden, Red Rocks (5) (2000–2). Assessed at $12 million, it’s the most valuable painting that may remain in Linda Macklowe’s possession, according to court papers. Courtesy of Matthew Marks Gallery.

The process to sell the Macklowe collection was well underway early last year, with Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips all clamoring for the prize. But then the pandemic hit and the collection’s court-appointed receiver Michael Findlay put the plans on ice.

Earlier this summer, as the art market rebounded and the vaccination rate accelerated, Sotheby’s and Christie’s were asked to submit their proposals again, according to people familiar with the process. The market has been abuzz ever since. Did Christie’s get it? Did Sotheby’s?

There has been no official word yet—but the expectation among people familiar with the matter is that the collection will go to Sotheby’s. (Representatives for Sotheby’s and Christie’s had no comment. Findlay didn’t respond to requests to comment.) “I can’t wait to scream that from the rooftops,” one Sotheby’s staff member said.

Any screaming will have to wait, however, until the legal decision is made by the court—or, as one dealer put it, “until this deal is signed in concrete.”

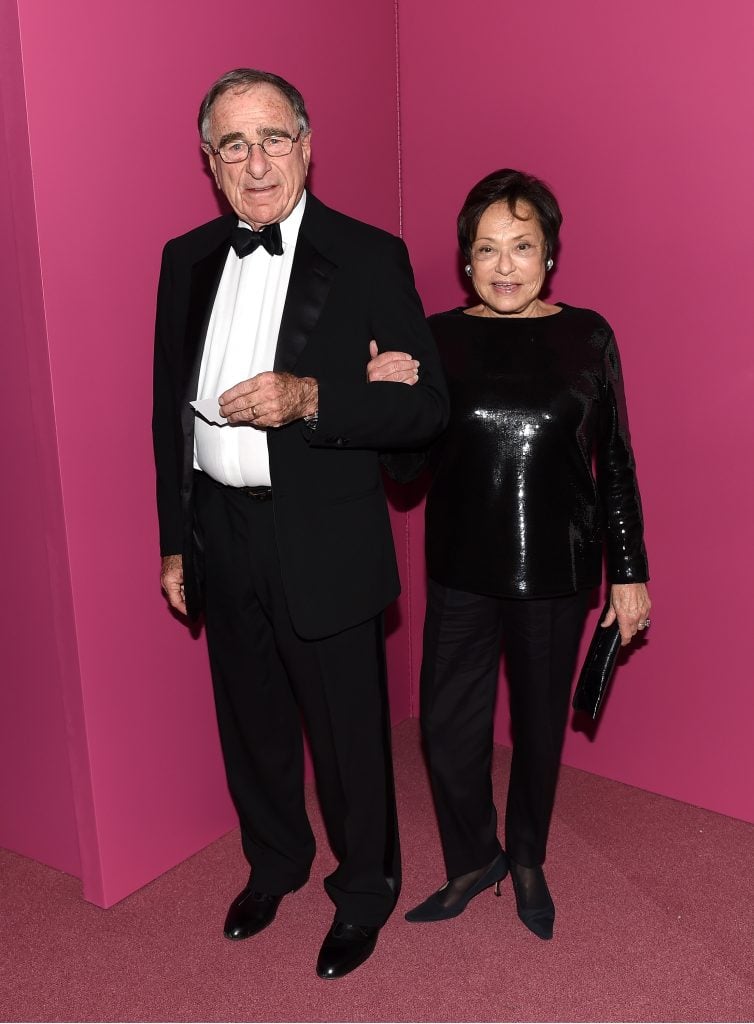

Michael Findlay. Photo: Victoria Findlay Wolfe.

The court is likely to make its determination of how to proceed based on the recommendation of the receiver, according to Thomas Danziger, an attorney who is not involved in the case but has represented divorcing spouses with valuable art collections.

The receiver’s presentation to the court is expected to be followed by a hearing, during which both parties will have a chance to voice their questions and concerns, opposition and support. After that, the court will make a decision about the sales strategy, Danziger said.

There may be delays. Linda Macklowe filed several appeals since the court’s initial order to sell the art in 2018, objecting to the sale itself and the appointment of the receiver, according to court documents. So far, those motions have been denied.

Attorneys for Linda Macklowe didn’t respond to requests to comment. Harry Macklowe’s attorney Josh Schiller, a partner at Boies Schiller Flexner, declined to comment.

Time is of essence for many reasons. Both Harry and Linda Macklowe are in their 80s. The court’s three-year deadline to sell off the collection is due to expire next year. And if the sales are indeed to start in November, the winning auction house would need to get a jump on its marketing campaign and start lining up financial backers to reduce its risk. (The three-year deadline may be extended if the receiver asks for more time, which he may, since a collection of this size and value is likely to be offered over multiple seasons.)

The winning bid is expected to come down to financials such as the guarantee offered by the auction houses and the split of the upside granted to the sellers.

“The question becomes if the auction house is giving all the money to the consignor or makes a return,” Danziger said, speaking broadly about top-end deals. “At the most aggressive levels, the consignor is effectively renting the hall from the auction house and is taking all the revenue.”

At the peak of the auction wars in the mid-2010s, the houses would often forgo profit for the privilege of selling a masterpiece. There may be more emphasis on dollars and cents during the pandemic, as Christie’s and Sotheby’s had to cut staff and adjust to reduced revenues.

Patrick Drahi, Sotheby’s new owner, in 2016. (Photo by Christophe Morin/IP3/Getty Images)

Sotheby’s—and its new billionaire owner Patrick Drahi—has more to prove. The company had been trailing Christie’s for more than a decade until last year. It has also recently seen an exodus of key executives in postwar and contemporary art, including the head of its global art Amy Cappellazzo.

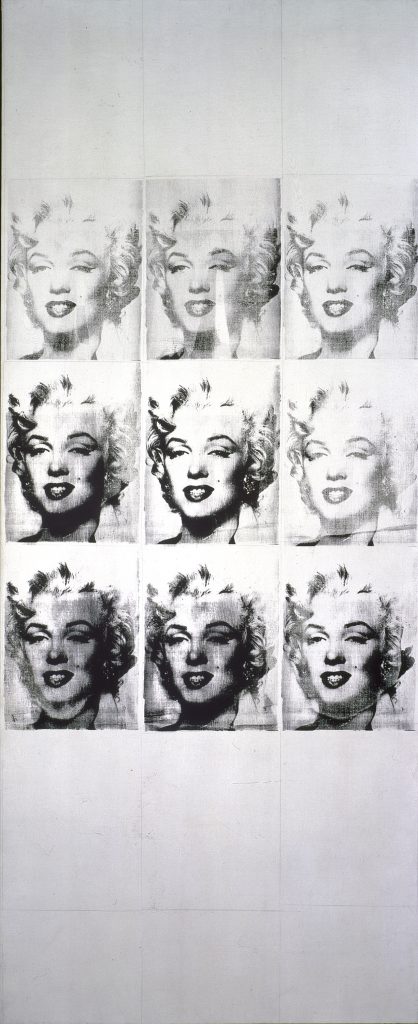

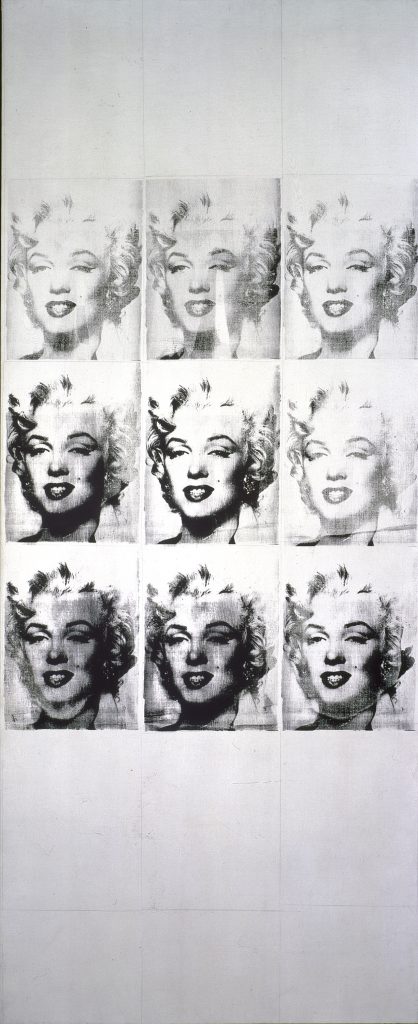

The market’s response to the collection—which includes such treasures as Andy Warhol’s Marilyn (9 Times) [Nine Marilyns] (1962), estimated to be worth around $50 million—is another unknown. Taste has begun to change as new buyers pour into the market. In May, the postwar collection of Texas philanthropist Anne Marion didn’t spark major fireworks, while paintings by artists of color including Jean-Michel Basquiat, Robert Colescott, and Matthew Wong ignited heated bidding wars.

Andy Warhol, Marilyn (9 Times) [Nine Marilyns] (1962) from the Macklowe Collection. Photo: Richard Gray Gallery.

Nevertheless, experts note, there remains a strong appetite for the very best postwar treasures. “Even with the post-COVID universe of NFTs and super-contemporary, there’s still vital global interest in masterpieces of 20th century art,” said Andrew Terner, a New York private art dealer.

Will the Macklowe works fit the bill? While the quality is stellar and most have spent decades off the market, the collection is also a known entity because of the legal drama and the trail of public documents outlining the works and their valuations.

“The question is whether it’s perceived as fresh or not,” said one auction executive. “It hasn’t been available and yet everyone knows what it is.”

Take a closer look at some of the collection’s highlights below.

Magnifying Glass

Magnifying Glass

Alberto Giacometti, Le Nez (1949)

The bronze sculpture ‘Le nez’ by Alberto Giacometti throwing a shadow at Schirn art hall in Frankfurt/Main, Germany. (Photo by Boris Roessler/picture alliance via Getty Images)

This sculpture drew the most divergent estimates from Harry and Linda Macklowe’s experts, with one valuing it at $35 million and another at $65 million, according to court papers. This piece depicts a head suspended inside a hollow rectangular cage. Its outrageously long nose extends beyond the confines of the prison-like structure. The Guggenheim Museum published the image of the work on the cover of its Giacometti exhibition catalogue in 2018.

Mark Rothko, No. 7 (1951)

The eight-foot-tall canvas features three horizontal bands of pink, yellow, and orange. Prices for the Abstract Expressionist peaked in 2012, when his painting from the collection of David Pincus fetched $86.9 million. In recent years, more somber works came to market and have been met with muted interest. In May, a blue Rothko sold for $38 million at Christie’s, falling short of the $39.9 million it fetched in 2014 when it was sold as part of Bunny Mellon’s estate at Sotheby’s.

Jeff Koons, Vest With Aqualung (1985)

Jeff Koons, Aqualung (1985). Courtesy of Christie’s Images, Ltd.

One of 12 works by Koons in the couple’s collection, this bronze had been estimated at $10 million by Harry’s art expert and $11 million by Linda’s. Although Koons’s stainless steel bunny sold for $91 million in 2019, making him the most expensive living artist at auction, his market has cooled off substantially since then. At a recent Phillips sale, a sculpture from his “Gazing Ball” series estimated at $400,000 to $600,000 was offered without a reserve, which means it could hypothetically have sold for as little as $1 (it went on to fetch $1 million). The Macklowe collection also includes a “Gazing Ball” work, estimated at $1.8 million.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

Magnifying Glass

Magnifying Glass