Since the beginning of 2021, the NFT art community has existed somewhere between a bohemian utopia and a crypto-gold rush. And in a world where volatility is the only constant, the unrestrained early enthusiasm around NFTs has given way to some harsh legal and technical realities. While there have yet to be any significant court rulings relating to NFTs, inevitable high-profile disputes in the non-fungible art marketplace have begun to emerge.

On March 2, the artist Ali Sabet auctioned an original digital artwork as an NFT titled Quarantine Magic in Motion. The piece, a one-minute animated, digital collage of colorful skulls, faces, words, and macabre images, was minted and offered for sale in three editions. (What does it actually depict? It’s a little hard to explain.) The first edition sold almost immediately for 10 ETH, a popular cryptocurrency (valued at approximately $15,000 at the time). The other versions were both purchased in the following days for comparable amounts. As is typical for NFT transactions, no intellectual property was transferred to the buyers, and no guarantees were made about the scarcity of the three “prints.” The buyers of these editions were presumably aware of this fact given their relative sophistication with this emerging market.

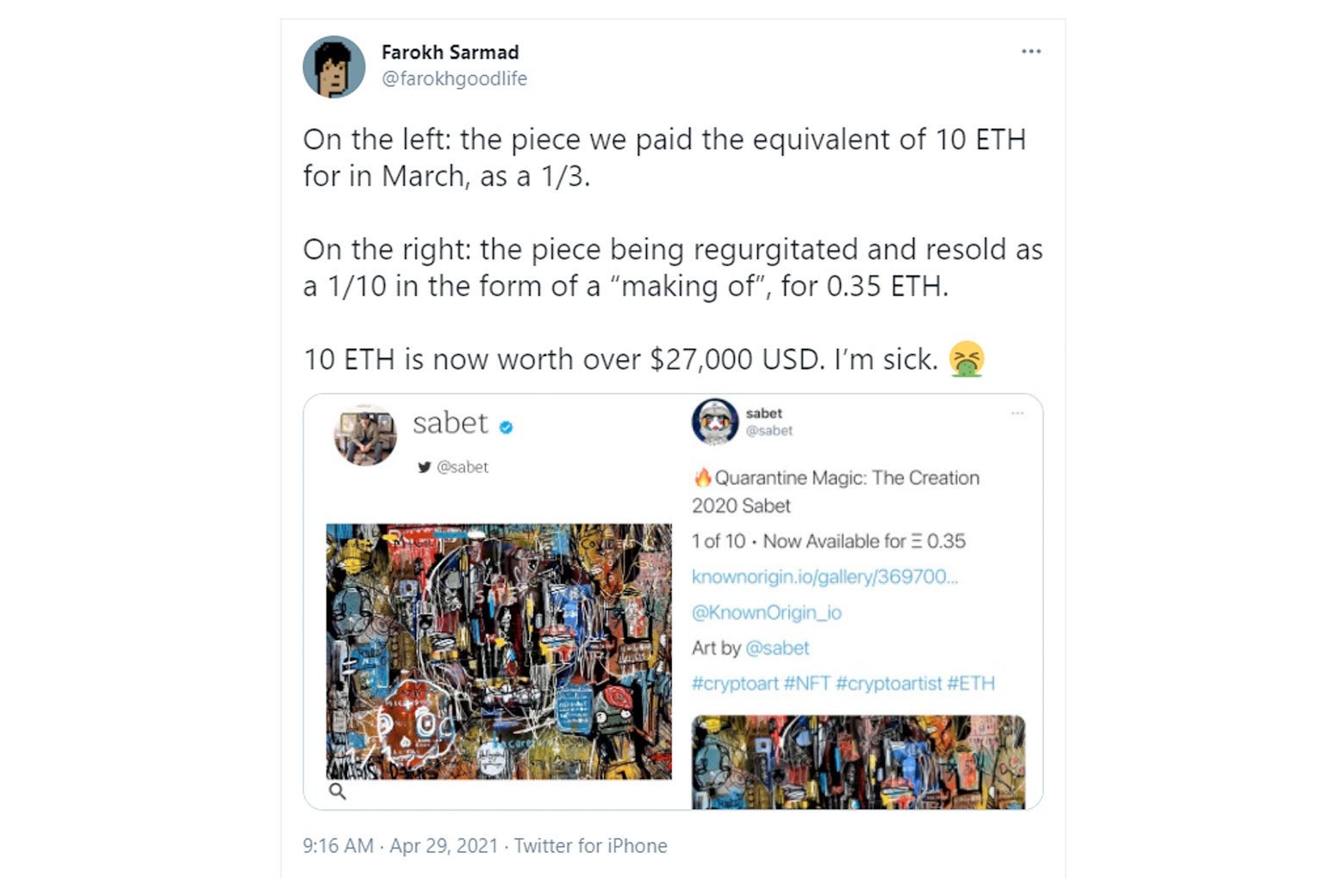

Nevertheless, drama erupted two months later when Sabet sold a strikingly similar NFT entitled Quarantine Magic: The Creation 2020. The second artwork was also an animated piece that showed the digital “painting” being created over time, and it sold for a fraction of the price of the original. Unsurprisingly, the release of the secondary work concerned the original buyers as well as other members of the digital art community—notably NFT promoter and activist Farokh Sarmad. Sarmad is an NFT enthusiast and known Clubhouse personality who has promoted artist NFT drops in social media and is an impassioned collector. He’s also a friend of Paolo Moreno, who purchased one of the Quarantine Magic in Motion editions.

Farokh publicly condemned Sabet for selling the Quarantine Magic “re-makes” and requested as a remedy that Sabet return the money to the original purchasers of the Quarantine Magic in Motion piece and burn the NFT—i.e., destroy the token and remove it permanently from the blockchain.

When reached for comment, Sabet would not answer any questions relating to the dispute or about Paulo or Farokh specifically. The matter was reportedly resolved with lawyers, though the terms of the settlement, if any, are not public.

Legally speaking, it is unclear whether Santos or the other “original” NFT purchasers had any viable claims against Sabet for selling the subsequent works. By law, Sabet retained all copyright to the original work, which includes the right to create and sell derivative works. The original purchasers of Quarantine Magic in Motion may have had legal recourse in the form of common law remedies like fraud or misrepresentation or violation of state consumer protection laws or U.S. securities laws. But such claims are very challenging to prove in these types of circumstances. Nevertheless, NFT creators and platforms would be wise to consider the potential legal ramifications of these products, especially as artists push the boundaries of what they create as NFTs and how they are marketed.

As with the analogue art world, artists often sell limited edition prints or copies of their work but reserve the right to distribute additional copies at any future time. For example, a photographer who auctions 10 limited edition prints of a single photograph is entitled to sell future copies of the work on postcards, T-shirts, or even “identical” copies in exactly the same size and format as the original limited-edition piece. But as a matter of traditional art culture, this is considered declassee and rarely done with high-profile works. Creating nearly identical reproductions would damage the reputation of the artist—and irrespective of legality, that is a sufficient deterrent. Moreover, some galleries or auction houses would likely refuse to display or sell these copies for fear of promoting poor artistic practices.

Part of the problem with NFTs is that there is not yet any shared culture around reproductions or derivative works of short video, animations, or audio-visual works that derive their primary profit potential from NFT sales. For now, the primary mechanism for enforcing norms and punishing bad actors is via internal policing in the community, primarily through shaming, and almost exclusively on social media platforms. In this sense, the NFT community currently resembles the stand-up comedy world, where joke-stealing is primarily enforced through the tight community of performers and venues.

Central to the NFT economy is the abstraction of artificial scarcity. Part of the core ethos of blockchain advocates is in the belief that the technology cannot be gamed or manipulated. The medium (of exchange) is the message. But as with other digital files, digital art can be copied infinitely without degradation. This inevitably shapes the market for digital goods, from software to media to art.

Notably, there are legal and technical solutions to these problems. One way is through the use of “smart contracts” to transfer rights or restrict the way both the artist and the purchaser display, copy, or exploit the work. For example, artists could offer, or purchasers could demand, a limited transfer of copyright or license to NFTs in a smart contract linked to the NFT. Similarly, an artist could guarantee that substantially similar works would not be sold as NFTs.

However, transfer of copyright is relatively unchartered territory in the art world. And many artists are understandably reluctant to sell off their intellectual property rights, especially without careful attention to the legal details. Moreover, smart contracts on the blockchain are still in their infancy. They can be expensive to implement and difficult to enforce, especially when a material part of the transaction occurs outside of the digital ecosystem.

In the meantime, NFT purchasers will likely have to rely primarily on artist reputations and they are wise to abide by the ancient adage “caveat emptor.” One thing that’s certain is that these controversies will not be a rarity.

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.