Art World

These Artists Made It Into Two of the Year’s Three Biggest Exhibitions—Have You Heard of Them?

See who made it into more than one of this year’s most prestigious artists lists.

See who made it into more than one of this year’s most prestigious artists lists.

As one of the busiest years for art in a decade starts winding down and the dust kicked up by the international jet setting art crowd begins to settle, certain takeaways from the Big Three—documenta 14, the 57th Venice Biennale, and Skulptur Projekte Münster—come into view.

One thing that can be said about the curatorial approaches taken by Adam Szymczyk and his team at documenta 14, Christine Macel at Venice, and to some extent, Kasper König and his team in Münster, is their efforts to eschew market pressures and established canons in favor of a diverse list of participating artists, with many names thus unfamiliar to even seasoned art insiders.

Having compared the artist lists of the three major art events, artnet News has noticed eight figures who appeared in two out of the Big Three this year. And while not entirely off-the-radar, the list includes names that may be new to many. (In regards to the artist list for documenta 14, we’ve only looked at the names listed on the quinquennial’s website, excluding artists that have contributed to the TV and radio programs.)

We delve deeper into these artists’ practices to contemplate why they were considered worthy of inclusion by the curators of at least two of these major shows, regarded in turn as deeply thought-through statements about the state of the art in our day and age. How do their ideas fit into the Now? And how well do you know their work?

Nevin Aladağ. Courtesy the artist and WENTRUP, Berlin. Photo Trevor Good.

Medium: Sculpture, Installations, Sound

Participation: documenta 14; 57th Venice Biennale

Gallery representation: Wentrup, Berlin; Rampa, Istanbul

Nevin Aladağ, Music Room (Athens), (2017). Installation view, documenta 14, Athens. courtesy Wentrup. Photo Trevor Good.

Trained as a sculptor, Aladağ’s work often involves sound as a means to explore the invisible yet very real social and political boundaries that govern public spaces and interactions. For the Athens leg of documenta 14, Aladağ built musical instruments out of vintage wooden furniture, invoking cosy, domestic interiors, which were played by musicians at the Athens Conservatoire—where they are installed—on opening day. A similar motif also features in her work for Venice, where she’s showing a video collage of instruments ingeniously set up on the streets of Stuttgart, where she grew up, so that they seem to play themselves—for example, a tambourine shaking because it is attached to the head of a playground rocking horse. In Kassel, Aladağ drew on the ornamental geometries of Jalis—perforated screens used as architectural elements—recreated in glazed ceramics in soft pastels, the preferred hues for bathroom tiles in 1950s Germany.

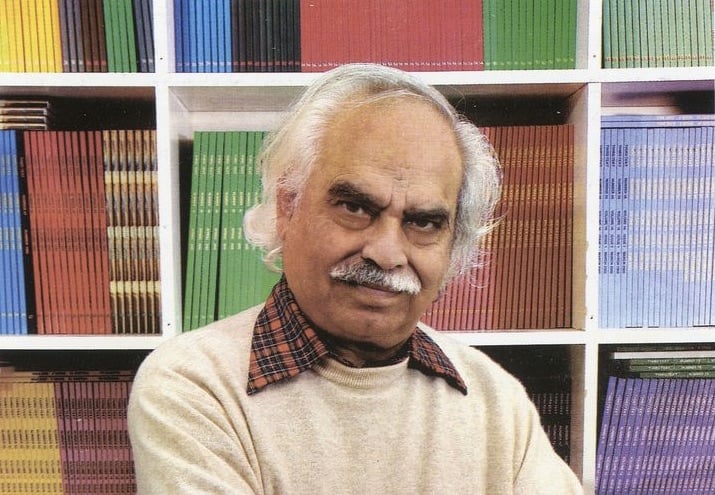

Rasheed Araeen. Courtesy Aicon Gallery.

Born in 1935 in Pakistan, lives in London

Medium: Sculpture, publishing

Participation: documenta 14; 57th Venice Biennale

Gallery representation: Aicon Gallery, New York; Rossi & Rossi, London, Hong Kong;

Rasheed Araeen, Zero to Infinity in Venice, (2016-17), installation view, Arsenale, 57th Venice Biennale. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia, photograph Italo Rondinella.

Araeen, originally trained as an engineer, is a pioneer of British minimalist sculpture and land art, and the publisher of the magazines Black Phoenix (1978-9) and later, Third Text (1987), and Third Text Asia (2008), which were influential in asserting post- and de-colonial positions overlooked in the canonized narrative of western Modernism. At documenta 14 in Athens, he invited the public to enjoy a communal meal under colorful canopies reminiscent of traditional Pakistani wedding tents. In Kassel, he’s presenting a reading section constructed out of modular, sculptural wooden cubes in a variety of bright colors, where issues of his publications are laid out for viewers’ perusal. Similar sculptural elements are also on view at the Arsenale in Venice; during the show’s preview, performers built temporary constellations out of them.

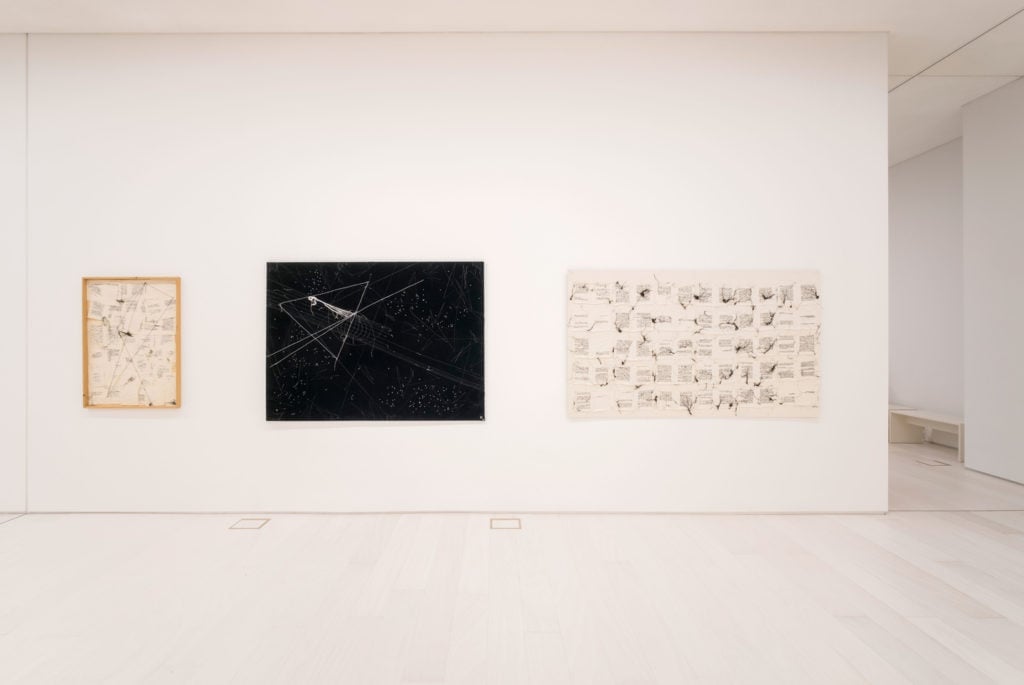

Nairy Baghramian. Courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery.

Born 1971 in Iran, raised in Germany, lives in Berlin

Medium: Sculpture

Participation: documenta 14; Skulptur Projekte Münster,

*was also Included in Okwui Enwezor’s 56th Venice Biennale in 2015, and in Skulptur Projekte Münster 2007

Gallery representation: Marian Goodman Gallery, New York, Paris, London; Kurimanzutto, Mexico City; Galerie Buchholz, Cologne, Berlin, New York

Nairy Baghramian, Privileged Points. Courtesy Skulptur Projekte Münster 2017. Photo by Henning Rogge

Most readers will be familiar with the sculptor’s evocative pieces, which have been shown in major institutions and biennials around the world. Her mixed-media sculptures meld a host of dualities: they can seem strangely familiar, at once comical and sublime, fragile but not weightless, grounded in political thinking and at the same time poetic. In her work, the Iranian-Armenian Baghramian, who grew up in Germany, points to the resonance of power in the spaces we inhabit. At documenta 14, she’s showing two sculptures relating to the life and work of the late American writer Jane Bowles. (In Athens, Baghramian is showing a new piece from 2017, whereas in Kassel, an earlier work from 2002.)

Meanwhile, in Münster, for her second participation at the important sculpture decennial, the artist installed two pieces in the front and the back court yards of an 18th-century baroque building. Titled Privileged Points, the two sculptures’ discrete elements are actually not yet welded together—this completion of the works will only take place if and when the city decides to keep the site-specific pieces at the end of the 100-day show.

Anna Halprin. Photo by SCalhoun, Wikimedia Commons.

Born 1920 in the US, lives in California

Medium: Dance, movement therapy

Participation: documenta 14; 57th Venice Biennale

Gallery representation: none

Anna Halprin, Planetary Dance, (1981-2017), performance filmed by John and Marguerite Veltri. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia

Is it a coincidence that a figure from the annals of modern dance and its more obscure fringes of therapeutic movement rituals suddenly appeared in two major shows this year? Maybe not. In 2011, Christine Macel curated the critically acclaimed show “Danser sa vie” at the Centre Pompidou, where Halprin’s work appeared in a section that also included Merce Cunningham and the Judson Dance Theater, and argued for a reading of dance as visual art. As for documenta 14, the curators’ focus on the political body served as a framework for her inclusion.

However, it was easy to miss the presentation of archival documents and sketches by Halperin at the documenta Halle in Kassel, which presented scores for dances, facsimiles, and sketches behind glass vitrines. Photographs of performances by Anna and her late husband Lawrence Halprin are shown in Kassel and Athens, too. At the Arsenale in Venice, however, documentation of Halperin’s work is prominently displayed, especially her annual Planetary Dance (1981-), a community ritual that revels in the natural world as a sacred space, and asserts women’s right to be free from sexual violence. (As artnet News contributor Hettie Judah writes, the work commenced as an act of cleansing to “reclaim” a mountain near San Francisco on which a number of women had been murdered).

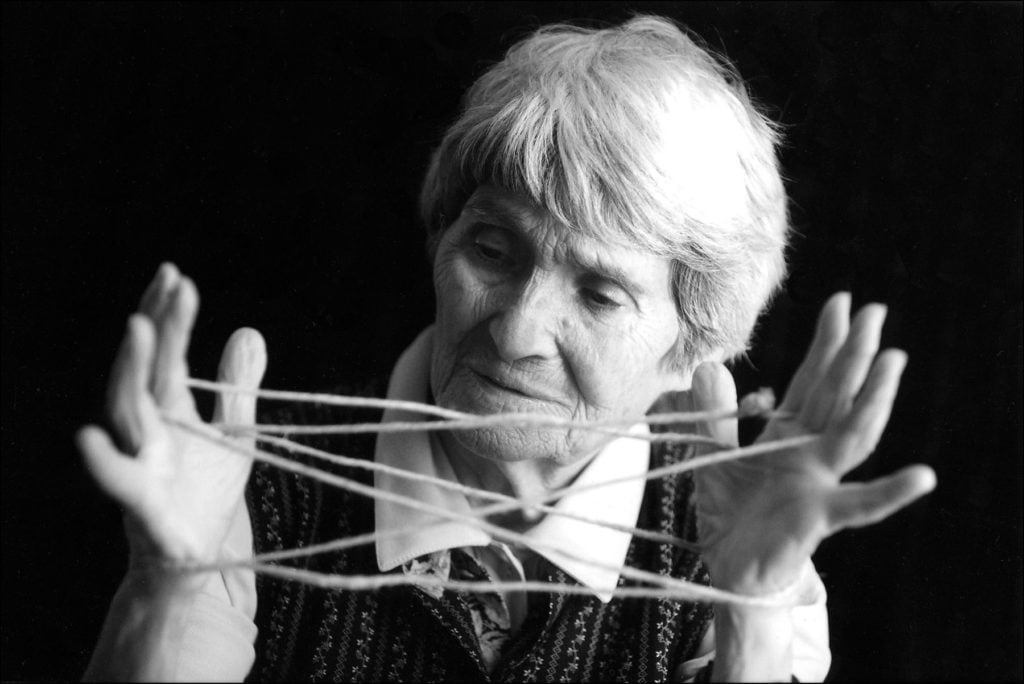

Maria Lai

1919–2013, lived and worked in Sardinia, Italy

Medium: Drawing, painting, textile, weaving

Participation: documenta 14; 57th Venice Biennale

Gallery representation: Nuova Galleria MORONE, Milan; Isabella Bortolozzi Galerie, Berlin

Maria Lai, installation view at documenta 14, Athens. ©Maria Lai/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017. Photo Mathias Völzke.

The work of the late Sardinian artist relates to the insularity of her craggy native island, its community—especially the identities of women there—and literature. Textile and yarn threading through a site-specific installation, a performance, or the pages of one of her “sewn” books—whose open threads spill from the paper towards the viewers—all relate to her central notion of art’s healing qualities.

In Athens, photographic documentation of her community performance To tie oneself to the mountain (1981) features alongside drawings and sewn canvases, while in Kassel, two of her sewn books are on view at the Neue Galerie as well.

Similar works are shown in Venice, along with some of her delicate-looking books made of bread and thread. Yet the works seem more vibrant here, given more room to unfold. What’s more, the seminal performance from 1981 is shown here again through photo and video documentation, where the Italian island’s residents’ obvious enjoyment of engaging in the playful, symbolic tying of their homes to island’s landscape is infectious.

Emeka Ogboh, Courtesy the artist, photo: Ugochukwu Nzewi

Born 1977 in Nigeria, lives in Lagos and Berlin

Medium: Sound art

Participation: documenta 14; Skulptur Projekte Münster

*was also Included in Okwui Enwezor’s 56th Venice Biennale in 2015

Gallery representation: none, shockingly

Emeka Ogboh, The Way Earthly Things Are Going, (2017), installation view, Athens Conservatoire (Odeion), documenta 14, photo: Mathias Völzke

Having participated in the 2015 Venice Biennale, and this year, in documenta 14 and Skulptur Projekte, Ogboh already has the major shows in an artist’s career under his belt, but shockingly, the artist, who works primarily with sound installations, is not represented by a gallery. His work for the Athens leg of documenta 14 is one of the most impressive pieces in the show: Inside the disused concert hall of the Conservatoire building, Ogboh presented a jarring installation that melds a real-time LED display of the world’s stock indexes with the rich soundscape of a traditional Greek song.

In Münster, Ogboh installed a sound piece under a busy bridge leading to the central station. There, he pays homage to the legendary (blind) musician, instrument builder, and poet Moondog, who relocated from New York to Germany in 1974, and died in Münster in 1999, where he is also buried. Ogboh collaborated with people who were close to Moondog, and wove his scores and poetry into a soundscape that, once noticed, turns the urban space and passers by into essential elements of the artwork.

For Kassel, he brewed Sufferhead Original—a stout with an alcohol content of 8.2 percent that ignores the German Purity Law—as a reflection on migration in Germany, and the culinary clashes that occur when moving to a new continent.

Koki Tanaka. Photo Makiko Nawa.

Born 1975 in Japan, lives in Los Angeles and Kyoto

Medium: Video, installation, socially-engaged practice

Participation: 57th Venice Biennale; Skulptur Projekte Münster

Gallery representation: Vitamin Creative Space, Guangzhou; Aoyama | Meguro, Tokyo

Koki Tanaka, Of Walking in Unknown, (2017). Documentation of action, objects, HD video, color, sound, 23’26. 57th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, Viva Arte Viva. Photo Andrea Avezzù

Having represented his native Japan at the 55th Venice Biennale in 2013, Tanaka was also awarded “artist of the year” of the Deutsche Bank two years later. His work deals with mundane, everyday objects that are cast in surprising relations to social issues, and used as catalysts to explore questions about communities, communication, and ethics. Since the nuclear catastrophe of 3/11, however, his work began to focus on the temporary communities and alliances produced by crises.

At the curated show at this year’s Venice Biennale, Tanaka directly addresses the disaster in Fukushima; a video work projected within an installation shows a journey that the artist took from his home in Kyoto to the nearest nuclear power station. In Münster, he adopted a more direct activist approach and ran workshops (and a community kitchen) with Münster residents of different generations and origins to meet and converse. His pieces there, How to Live Together, and Sharing the Unknown, are video documentations of these encounters.

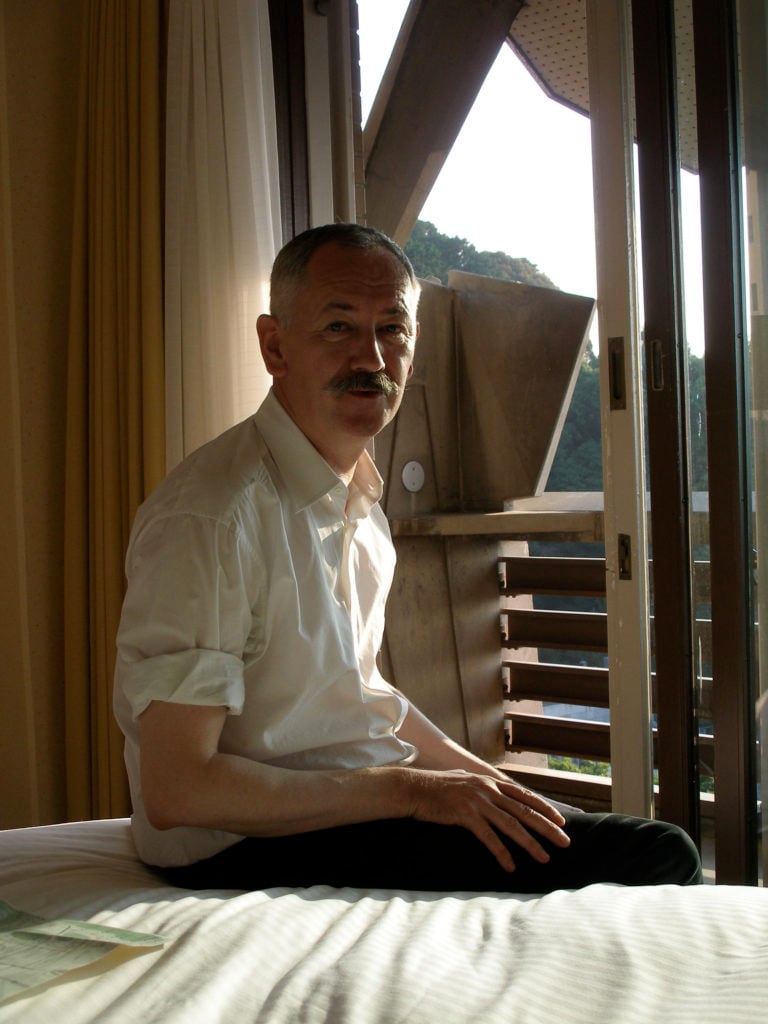

Cerith Wyn Evans. Photo Ali Janka, courtesy White Cube.

Born 1958 in the UK, lives in London

Medium: Conceptual art, sculptor, filmmaker

Gallery representation: White Cube, London; Galerie Buchholz, Cologne, Berlin, New York; Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo

Participation: 57th Venice Biennale; Skulptur Projekte Münster

Cerith Wyn Evans, A Modified Threshold… (for Münster). Existing church bells made to ring at a (slightly) higher pitch, ©Skulptur Projekte 2017, Photo Henning Rögge.

One of the better-known names on this list, Evans has participated in numerous biennials and major shows throughout his career. He is a conceptual artist who often deals with language and perception, but first became known as a filmmaker: he worked with Derek Jarman, collaborated with Michael Clark’s dance company, and made music videos for bands like The Smiths and Throbbing Gristle.

At this year’s Venice Biennale, he is showing an older piece in the Giardini—the film Firework Text (Pasolini) from 1998. Shot on the beach where Pier Paolo Pasolini was murdered, the film shows men building a wooden sculpture to support a text segment. It is then lit up and is slowly consumed by the flames.

For Münster, Evans created a new work that’s also a bit of a challenge to detect: in the bell tower of a Brutalist church located just outside the city he installed a cooling device that effects the pitch of the bells’ toll. The ringing therefore sounds as if it were the dead of winter throughout the 100 days of this summer show.