Opinion

The $14 Million Flip, and What the London Day Sales Foretell for the Near Future

artnet News's dauntless columnist ventured to the London auctions to sift for clues among the remainder bins.

artnet News's dauntless columnist ventured to the London auctions to sift for clues among the remainder bins.

Imagine Janet Yellin—or the head of your respective Federal Reserve—calling to say that you’ve been granted free rein of a currency-printing press, with the lone caveat that it be enjoyed at your discretion. That has been the case, more or less, for a select few artists over the years, from Dürer and Rembrandt to Koons and Hirst, who have minted fortunes through their (often editioned) art. But the public wasn’t always so enamored of the notion of celebrity artists (or artrepreneurs) with business managers as muses. In fact, Richard Prince now employs an agent to act on his behalf in the direct-from-studio selling of his art.

Painters Bernard Buffet and Mark Grotjahn share more than striated brushwork. In 1956, a 28-year-old Buffet appeared in Paris Match posing with his chauffeured Rolls Royce in front of his gated villa—not unlike Instagram posts by Grotjahn kicking a beach ball on the grounds of his grand mansion among his fleet of Rollers. Buffet’s career never recovered from his blighted reputation for artistic insincerity, earned by painting scenes of ascetic austerity while living large and being driven in a set of wheels that set him back 4,500,000 francs (roughly $15,000 in the period). But the art world has gotten over its priggishness and grown to accept private planes as part and parcel of an artist’s life, right up there with being poor and crazy. Besides, I doubt any artist ever became financially well off by making wealth-creation their sole artistic ambition, including the lot mentioned above. Honestly.

In what could be one of the most audacious moves in recent market memory, a spec-u-lector purchased a $14 million Mark Grotjahn painting via a Sotheby’s private treaty sale, I’m told, and in the same breadth consigned it to Christie’s with no guarantee. The $14 million flip! Whether this would turn out to be prescient or preposterous remains to be seen; another slated to go on offer in May was also bought only months ago for $6,000,000. Call it art-market musical chairs. (A Sotheby’s executive, incidentally, refutes that the flip occurred, saying he asked the buyer point-blank and was told, “I’m not that stupid.”) Meanwhile, I sold a Grotjahn on behalf of a client directly to one of the big auction houses (i.e. not Phillips). By the way, if the level of assurances the houses require when buying on their own account were applied to normal consignors, it would, in the words of one specialist, “put them out of business.” Come the end of May, Mark Grotjahn will either be the next Peter Doig or Lucien Smith in the eyes of the market (which has been known on occasion to dissociate itself from the inherent worth of a work).

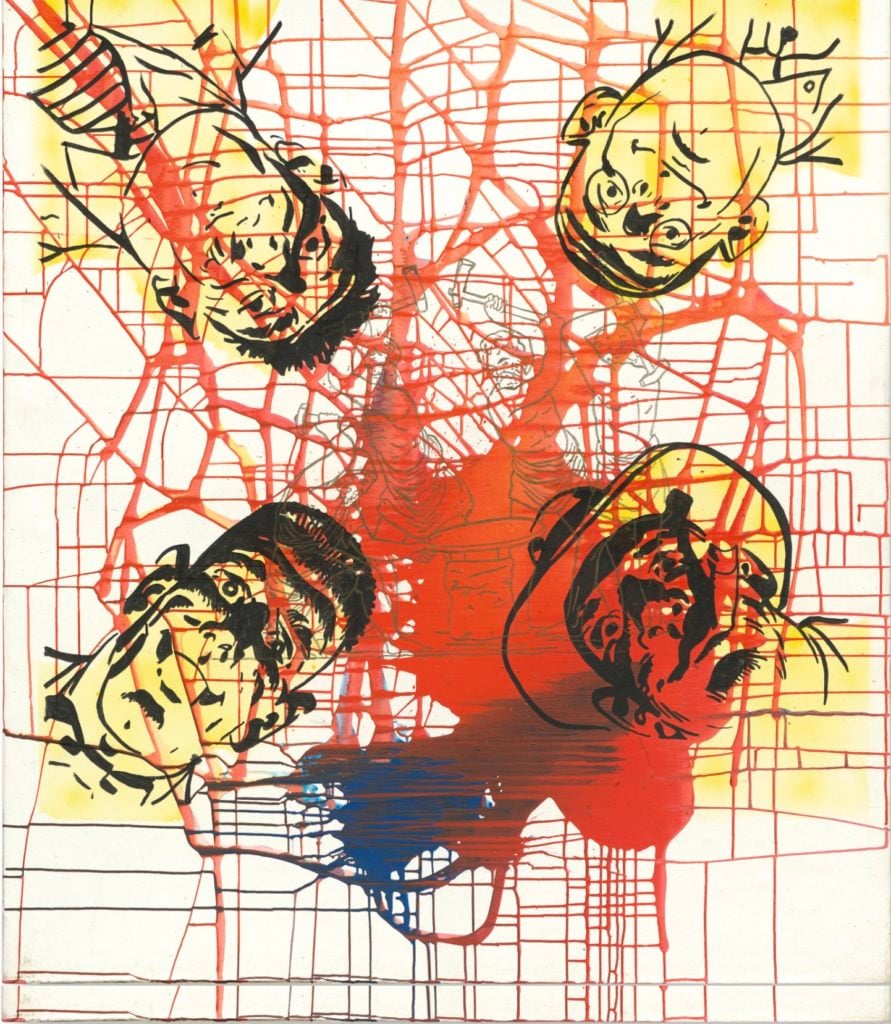

Buffet and Grotjahn. Courtesy Kenny Schachter

The February London auctions never amount to more than an appetizer for May in New York, the bellwether indicator of the market’s strength. Funny to think that when I first moved to the U.K. in 2004 there was speculation London would overtake New York as the center (or centre) of the art market. That’s before the bull in the china shop, i.e. China, came charging in—though Chinese are still wont to walk away from as many lots as they walk home with. London’s biggest contemporary sale, posted last week by Sotheby’s, brought in less than a single Modigliani reclining nude sold in New York a year and a half ago (to China). Though guarantees goosed proceedings along nicely, I disagree with Melanie Gerlis of the Financial Times that pre-selling works through guarantees limits the free market; rather, it’s an expression of an open market—that people have an option to pre-buy at a predetermined price.

Whatever your stance on the matter, you need to be an internet sleuth or Russian political hacker to navigate some of the auction house websites, if they work at all. I spent a full 20 minutes trying to download the full slate of Christie’s evening sale results, which proved futile. After a half-dozen attempts and as many reboots, I gave up. Aggravated to point of hysteria, I went as far as asking a friend to try, but she’d had the same problem days ago. François Pinault is closing Christie’s London’s Kensington outlet, firing staff—okay, a lean machine is a profitable auction house—but scrimping on the web in today’s age? I can’t even. Besides the annoyance of links failing to connect to their targets, the site crashed more than a Harrison Ford-piloted plane. So, I decided to peruse the day sales exclusively instead. I hope they take heed of my anguish and rectify the site by May. The app seems to work—maybe they are writing off desktops in favor of the direction of… kids.

Christie’s day-sale total, including buyer’s premium, was £16,316,312; Sotheby’s bested them with £16,665,725 (and bested them in the evening sale as well). Phillips, meanwhile, came in at £7,365,875, near the high end of their estimate as opposed to their miserable evening outing that a 40 percent plummet from last year’s February performance. I had to call Phillips for their results, which weren’t available on their site. Day sales are the art world’s sample sales, where last season’s goods (or lesser iterations of known works) wend their way to the market. While they’re great barometers of the market, glitz and glamor are in short supply. Not for the short attention-spanned, the sales are largely professionally attended undertakings that drag on more monotonously than a religious ceremony and not altogether differently; you have to make a leap of faith to stockpile—I mean, collect—a lot of this fare.

Phillips

I tried to give Phillips the benefit of doubt in a quote for a recent Telegraph article by Colin Gleadell, but it never ceases to amaze how regularly the house misses the mark—and makes me look (more like) a dunce for thinking they would consistently improve. Thanks. They would be better served as a solid day-sale-only company, and with a 5 p.m. “evening” sale (more like a matinee performance) slated prior to the onset of Sotheby’s later that night, they are fast approaching that strategy no matter what they deign to name it. Phillips is the early bird special(ist), like the cheap-eats offerings for the age-challenged in the Miami of yesteryear. Regardless, I applaud any and all efforts to augment transactional avenues, exit strategies, and liquidity-enhancers—even from Bonhams, now teething in the international contemporary-art arena and a possible heel-nipper of Phillips in times to come.

Picasso work on paper at Phillips day sale. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter

In their actual day sale, Phillips failed to sell a tiny minor (but cool) Picasso and a Gerhard Richter painted book. The Picasso, Le Photographe, a gouache and pencil on paper depicting a photographer shooting a nude in his studio, was executed in 1964 and estimated at £150,000-200,000; the Richter, War Cut II (2004), consisted of oil on a linen book, was estimated at £80,000-120,000. Both passed. Phillips’s wares can resemble a clearance sale on the front lawn of a suburban tract house.

A pair of Ai Weiwei’s Fairytale – 1001 Chairs, pegged at $45,000 at New York’s Armory fair, were estimated at £12,000-18,000 at Phillips and sold for £13,750 ($16,800) while another set from the same edition was estimated at £10,000-15,000 at Christie’s and sold for £21,250 ($25,967). Go figure. The adage has rung true from the day Phillips first hung a shingle and began hawking art: buy at Phillips, by all means—but if you should need to sell, call Sotheby’s or Christie’s. As to the differences between Sotheby’s and Christie’s, there are none. They are fungible on a looping rollercoaster as to who’s on top in a given year according to the winds of shifting market vicissitudes.

Phillips did sell a Frank Stella recreation in miniature by Richard Pettibone, entitled Frank Stella Takht-i-Sulayman 1967 (1972), with an estimate of £15,000-20,000 for a whopping £106,250 ($130,000). And more impressively, they managed to bring a Zombie back to life (again) in the case of David Ostrowski, selling F (Bilder die Ähnlichkeit haben mit meinem Vater) from 2012 (with an estimate of £20,000-40,000) for £52,500 ($64,000).

David Ostrowski painting at Phillips day sale. Courtesy Kenny Schachter

George Condo is on fire. A 2005 painting of a woman’s torso with two nasty-looking stacked dog heads for a face, entitled Jean-Louis’s Girlfriend (and I trust Jean-Louis and his special lady have a sense of humor), was estimated at £150,000-200,000 and sold for £389,000 ($475,358), while a much more tasteful work on paper reached more than three times the low estimate. It’s still cheaper than the primary market, though, so we’re not exactly there yet. Another, The Colorful Tailor from 2008, estimated at £60,000-80,000 made £185,000 ($226,000). But don’t get me wrong (like I got it wrong in the Telegraph): Phillips has a way to go to be a winner—but thankfully their web site functioned flawlessly.

George Condo canvas at Phillips day sale. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter

Sotheby’s

The Sotheby’s day sale was a generally uneventful affair. David Hockney’s Beverly Hills Housewife from 1966, pencil and crayon on paper and estimated at £100,000—150,000, sold for £162,500 ($198,575) but is only worth noting due to the fact that the bulbous-nosed (à la a heavy drinker) and lantern-jawed housewife was faithful to the unsightly woman in the painting that the drawing was a study for. She was no beauty, but I wish I’d bought her.

A surprise was the six Banksy works on offer for the week, four from Sotheby’s and one each from Bonhams and Christie’s, that sold for a grand total of £894,250 ($1.1 million) against gross estimates of £360,000-520,000—so garnering more than 70 percent above the high expectations. Banksy stole the momentum from his friend Damien Hirst, who launched the street artist’s career by sucking up as many of his early pieces after meeting him as he could, like a hoover. Banksy surreptitiously opened a new intervention called the Walled Off Hotel in the occupied West Bank that was kind of epic no matter where you stand on the contentious Palestinian-Israeli issue. It’s short-term housing no one can argue with, boasting the “world’s worst view” of the ungainly cement security wall that dissects the country, figuratively and literally. Forum Auctions, an upstart U.K. company, has a further 22 Banksy editions on offer March 21st in London, so grab ‘em while you can.

Sigmar Polke at Sotheby’s evening sale. Courtesy Kenny Schachter

Two night sale stories are worth recounting. Sigmar Polke’s Die Schmiede (Smithy) from 1975 carried an estimate of £1,000,000-1,500,000 and sold for £2,408,750 ($2.9 million); the work was listed as “property of a private German collector.” One specialist proudly boasted to me and my client that the piece was the earliest extant example of Polke’s layering of imagery in the Picabia-esque manner that became a signature. Another less reverent Sotheby’s staffer offered us a more lurid accounting: Polke appropriated the image from a Nazi-infused graphic novel of a woman being hacked, thrown down a well, left for dead, and then leered at from above by four voracious men she mistakenly thought would save her (they were necrophiliacs awaiting her demise before having their way with her). Polke initially hung the work from the ceiling for further effect. Sorry… I’m only recounting what was told to me. By a Sotheby’s guy—he should be employee of the month.

Georg Baselitz’s With Red Flag from 1965, estimated at £6,500,000-8,500,000 made £7,471,250 ($9.1 million), and was sold subject to such a surfeit of auction-house symbols that it would have helped to be an Egyptian hieroglyphic decipherer to figure it all out. There were six icons in the catalogue reflecting the fact that the painting was subject to “Irrevocable Bids,” that it was “Property Subject to an Artists Resale Right,” that it had been Imported from outside the EU to be sold at auction under temporary admission, that it was guaranteed, and that it was property in which Sotheby’s has an ownership interest. There was another runic emblem that I couldn’t even locate in the catalogue’s symbol key but later found out meant that the work will be located in Sotheby’s warehouse, post-sale. Good to know.

I heard from Deep Pockets that there was some typical mendacious art-world behavior behind the orgy of ciphers attached to the Baselitz lot, illustrating that dealers are great prevaricators, also known as fibbers (or, more colloquially, liars). Art Agency Partners, before Sotheby’s acquisition of the advisory firm, coaxed the painting from the private-dealing previous head of contemporary at Sotheby’s, Tobias Meyer, using a proxy to represent that the work was headed to a committed end-using collector (remember those?). It wasn’t and landed in Art Agency Partners’ speculative investment fund, which became all or part of Sotheby’s property before being ceremoniously dumped into auction at a record for the artist, which equaled a quantum jump from his previous top.

The pace of the art trade remains brisk, and though there are plenty of deals, steals are scarce. Obvious art by obvious artists that everyone covets, hand-in-hand, is fully priced, and then some. London may be a backwater of the auction market, but as a litmus test of what is shortly to come in New York the confirmation was unequivocal: I can’t and won’t vouch for Phillips, but I see big, headline grabbing sales ahead at the other two house. Let’s see.

Editor’s Note: A previous version of this story indicated that “word on the street” had it that the Baselitz lot remained in Sotheby’s possession after the sale. A Sotheby’s lawyer contacted artnet News to say that this was false, and pointed out that such an act of self-dealing would be illegal. We have removed that bit of unsubstantiated gossip from the piece.