Opinion

What to Make of MoMA’s Stand on Trump’s Travel Ban

A closer look at what the rehang actually means.

A closer look at what the rehang actually means.

This week, New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) rehung its prized Modern galleries, swapping out works by greats like Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso for works by artists from the Muslim-majority countries affected by President Trump’s travel ban.

It’s not exactly as if MoMA has draped itself in a “Muslim Lives Matter” banner. Still, this rapid response, conceived by curators Ann Temkin, Jodi Hauptman, and Christophe Cherix over the weekend of cresting outrage over Trump’s executive action, stands out as an unusually direct statement on current events for a major art institution—appropriately enough, since this is an alarming time. The Art Newspaper reports that the curators plan to integrate still more works in coming weeks.

The first wave of new artists are all either of a generation of post-war modernists—the Iranians Siah Armajani (b. 1939), Marcos Grigorian (1925-2007), Parviz Tanavoli (b. 1937), and Charles Hossein Zenderoudi (b. 1937), plus the great Sudanese painter Ibrahim El-Salahi (b. 1930)—or more contemporary figures: the architect Zaha Hadid (1950-2015), the painter Tala Madani (b. 1981), and the photo-conceptualist Shirana Shahbazi (b. 1974).

Consequently, their artworks are technically out of place where they appear, in MoMA’s Modern galleries, which are mainly devoted to the earlier part of the 20th century. Chronologically, the works should either be in the galleries opposite Andy Warhol and James Rosenquist, or displayed with the more recent art.

The logic of their placement lies in the need to make a statement: The Modern galleries are where MoMA keeps the crown jewels. Inserting the new works alongside the museum’s foundational treasures gives a certain kind of symbolic weight to the inclusion. It interrupts business as usual.

A man looks at artwork by Iranian artist Tala Madani’s Chit Chat (2007) at The Museum of Modern Art on February 3, 2017 in New York City. Courtesy of Angela Weiss/AFP/Getty Images.

I might, in a different mood, have questions about the curatorial choices made. For instance, Madani is known for small paintings depicting scenes of patriarchal brutality. Her hand-painted two-minute animation, Chit Chat (2007), installed opposite expressionist canvases by Chagall and Kirchner, depicts two of her characteristic subjects—balding Middle Eastern men, cyphers of a more general patriarchal authority for her—conspiratorially arguing, overseen by a devilish figure. At certain points, they puke yellow onto each other, as if literally overflowing with nastiness.

Lobbing such a work into the debate over the Muslim ban seems odd, since it could easily be used, out of context, to illustrate some ugly stereotypes about Iranians.

On the other hand, consider another of the added artworks, Shirana Shahbazi’s [Composition-40-2011] (2011), a large photo of three colored spheres on a black background, inserted into the galleries normally devoted to Marcel Duchamp. The connection, it seems, is that Shahbazi’s work shares a heady puzzle-character with the Frenchman, which seems apt.

![Shirana Shahbazi’s [Composition-40-2011] (2011) on view next to Marcel Duchamp's <em>To Be Looked at [from the Other Side of the Glass] with One Eye, Close to, for Almost an Hour</em> (1918). Image: Ben Davis.](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2017/02/shirana-shahbazi-1024x768.jpg)

Shirana Shahbazi’s [Composition-40-2011] (2011) on view next to Marcel Duchamp’s To Be Looked at [from the Other Side of the Glass] with One Eye, Close to, for Almost an Hour (1918). Courtesy of Ben Davis.

In other words, Shahbazi’s photo-conceptual work can be interpreted as representing a distrust in the Western audience’s ability to distinguish the nuances of representation—the same nuance that the inclusion of Madani’s grotesque animation demands.

In the end, it seems obvious that MoMA’s gesture is a blunt one because it is responding to a blunt, unrefined discourse. The statement is: You want to devalue people from Muslim countries? Well, we value them! The curators acted fast because the conversation was urgent. That seems worth applauding.

I do think, however, that there’s more to say about this act, and the history behind it.

The story that MoMA was built to tell is the story of Euro-American modernism. All by itself, this story is very much one of immigrants and refugees: Duchamp hopped the Atlantic to get clear of World War I; Willem de Kooning came to the US as a stowaway; Josef and Anni Albers fled the Nazis to the US; Arshile Gorky was a refugee from the Armenian Genocide; the list goes on.

Yet this is a story of mainly white European immigration. And one of the unintended side effects of MoMA’s emergency rehang is to remind you that there are other, non-Western modernisms, which have only been imperfectly incorporated into the story it tells.

Which brings me to the artists I was most excited to see here, El-Salahi, and the cluster of Iranian artists who found their creative voices in the early 1960s.

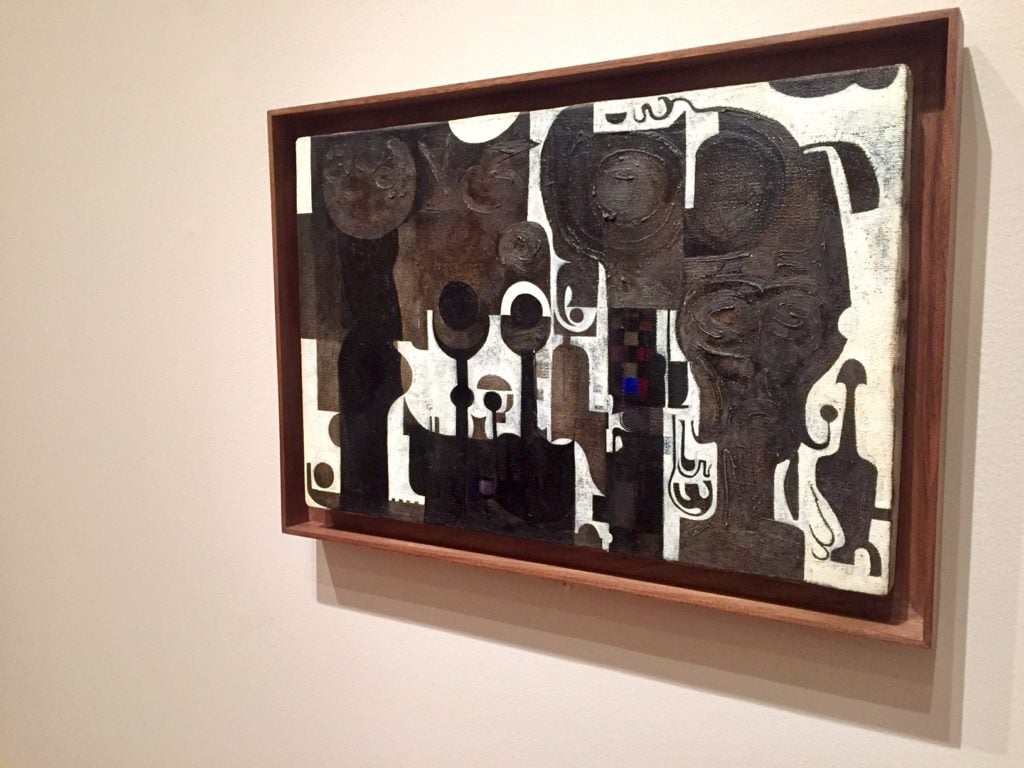

Ibrahim El-Salahi, The Mosque (1964). Courtesy of Ben Davis.

Seeing them highlighted is terrific, even if the way they are deployed doesn’t do them full justice. El-Salahi’s small black-and-white canvas, The Mosque (1964), is placed in the Picasso galleries, intended to play off of the Spanish artist’s interest in African art. But the lone, small work gives only a hint of the scale of El-Salahi’s achievement or his vision, the proximity to better-known Cubist masterpieces only accentuating the relative scarcity of familiar aesthetic context for his work.

Similarly, the Iran-born Charles Hossein Zenderoudi appears via a large work on paper in the Matisse galleries, which is meant to make sense because of the Fauvist great’s interest in Islamic decorative art. But the mellow tones of Zenderoudi’s K+L+32+H+4. Mon père et moi (My Father and I) (1962) look a little muted next to the famous exuberance of Matisse’s The Dance, one of the world’s most iconic paintings.

Visitors look at K+L+32+H+4. Mon père et moi (My Father and I), 1962 by Iranian painter and sculptor Charles Hossein Zenderoudi at the Museum of Modern Art on February 3, 2017 in New York City. Courtesy of Angela Weiss/AFP/Getty Images.

Like I said, it’s all better than nothing. But in a different world, giving the full due to these artists could make a truly vital point right now.

El-Salahi was one of the fathers of the Khartoum School in the Sudan (along with Ahmed Shibrain and Kamala Ishag). They brought a modernist freedom to the canvas, but self-consciously welded it with Islamic imagery and local vernacular culture, including decorative patterns, Quranic verses, and Sufi poetry.

“We had a problem then that separated the contemporary artist from the local public,” El-Salahi recalled in a previous interview. “I personally felt that a bridge had to be built to close that gap between the two parties.”

Zenderoudi, Tanavoli, and the other Iranian figures here are generally known as part of the Saqqakhaneh movement. The term “Saqqakhaneh” refers to Shi’ite shrines, small alcoves with a water dispenser where people leave religious offerings, decorated with various kinds of metalwork and devotional objects.

Parvez Tanavoli’s The Prophet (1964), with Umberto Boccioni’s Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913) in the background. Courtesy of Ben Davis.

Their mission was to create a strain of indigenous Persian modern art, welding the vitality of Islamic folk culture with various experiments. Indeed, if Zenderoudi’s color scheme doesn’t attain the unfiltered sensuality of Matisse, that is because, as Hamid Keshmirshekan has argued, it is very deliberately meant to evoke the characteristic tones of Iranian religious folk art: gold, green, ochre, orange, and red.

Both the Khartoum School in Sudan and the Saqqakhaneh movement in Iran would pioneer a turn towards “calligraphic modernism,” finding in calligraphy a tradition that could be organically developed into new forms of abstract art. More than that, though, what they shared was the spirit of region-wide ferment in the 1960s era, what Iftikar Dadi calls this the “heroic age” of “nationalist modern,” rejecting the idea that they had either to reiterate static tradition or be imitators of European innovations.

In Dadi’s words:

[T]he new culture was to be individuated, yet collective; it was to be completely modern in the sense of being in dialogue with artistic production in the industrialized world, yet it was also mandated to represent local histories and lived practices that were hitherto suppressed; and, above all, the new culture was to be emblematic of national specificity.

The point is this: These artists are important as examples not just because they are very accomplished figures who also happen to be from Muslim-majority countries. Given its proper historical context, their art rebuts the “clash of civilizations” stereotype of Islamic culture as chained to a past that is innately hostile to being integrated into the present.

We can’t have enough of those examples now. MoMA has started a conversation. It seems more urgent than ever not to leave it there.