Art World

Have Scientists Solved Mystery of the White Smudge on Munch’s Scream?

It isn't bird droppings, for starters.

It isn't bird droppings, for starters.

Scientists at the University of Antwerp in Belgium say they have solved the mystery of a white smudge on the surface of Norwegian painter Edvard Munch’s most famous painting, The Scream (1890).

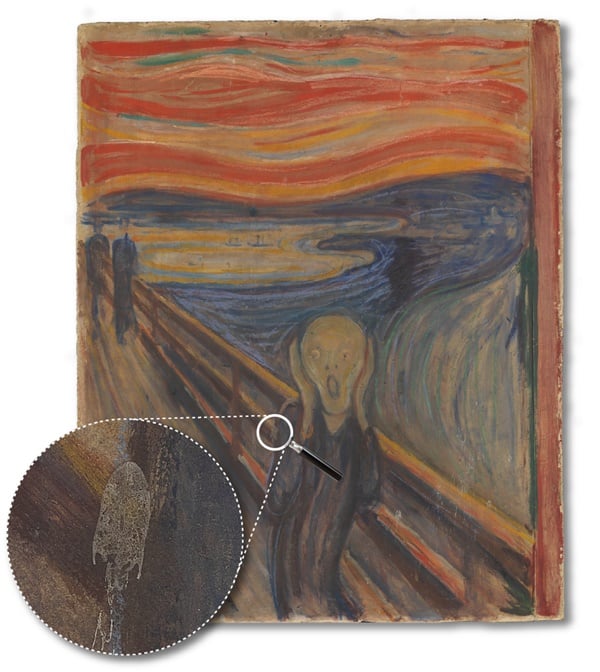

The smudge on the surface of The Scream.

The white mark that hovers above the right shoulder of the iconic screaming figure—rendered in wavy, expressionist strokes with his hands clapped to his head—is candle wax and not bird droppings, as a longstanding rumor had it. The painting in question is the earliest of the four versions that Munch executed.

Edvard Munch posing with paintings outdoors at Ekely (near Oslo). Courtesy University of Antwerp.

Late 19th-century photographs, such as the one above, show that Munch often painted outdoors and stashed paintings in a barely covered wooden shed. Following careful research, scientists at the university found that the white smudge was caused by wax, likely dripped from a candle in Munch’s studio that dripped on to the painting.

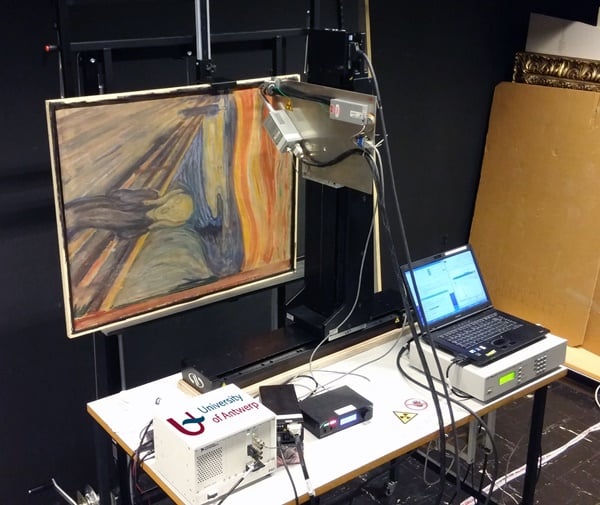

MA-XRF scanning in progress at the studio of Nasjonalmuseet. Courtesy of University of Antwerp.

Researchers analyzed the work using a machine they developed on their own, called a Macro-X-ray fluorescence scanner. The technology was used in the past to settle disputes over works of art by artists including Van Eyck, Rubens, and Van Gogh.

The non-invasive scans “ruled out the readiest paint option as no white pigments nor calcium was detected inside the enigmatic smudges,” according to the university.

“Bird droppings can pose a significant threat for monuments, outdoor statues … and brand new cars,” said Dr. Geert Van der Snickt, cultural heritage scientist at the University of Antwerp in a statement on the institution’s website. “‘But I did not associate it with easel paintings, and certainly not with quintessential masterpieces that are valued over 100 million dollars. This somewhat unexpected substance illustrates why the interface of art and science keeps me spellbound. Solving the mystery of the bird droppings on the Scream also demonstrates why our discipline has much equipment in common with forensic experts.”

A version of The Scream sold at Sotheby’s in 2012 for $119.9 million. This particular version is part of the collection of the Norwegian National Museum in Oslo. The painting entered the museum’s collection directly from the artist’s studio and “white splatters have always been present,” according to the university’s website.

“Using a synchrotron to identify wax is a bit like asking NASA to route turn-by-turn directions between New York and Boston,” conservator Jamie Martin, of Orion Analytical, told artnet News via email after reading about the University of Antwerp research. “But the important take-away is that conservators and conservation scientists (like me) often benefit from collaboration with scientists in other fields, whose curiosity—when piqued by projects like The Scream—may lead to development of new materials and techniques to preserve and interpret art.”