Analysis

13 Collectors Who Are Driving the Trend for Super-Sized Art

They provide a unique home for artists who dare to dream big.

They provide a unique home for artists who dare to dream big.

Contemporary art is big business. It’s also in the business of big: Collectors are ever more interested in snapping up the kind of massive, statement-making sculpture and installation work that formerly was the specialty of only the mightiest of museums.

During the recent Art Basel, fair boss Marc Spiegler told the Financial Times that the market for the kinds of showstoppers showcased in the fair’s signature Unlimited section of super-sized art was increasingly private. We asked ourselves, who are the pioneers of this new trend?

Here are a few of the names who’ve have been particularly big influences in funding supersized-art.

Per Kerkeby, Untitled (1994-2003). Courtesy Clingenbosch.

Joop van Caldenborgh

The Dutch chemicals magnate’s crowning glory is Clingenbosch, his own vast personal 50-acre sculpture park near the Hague, which will soon be supplemented by the Museum Voorlinden in Wassenaar, displaying around 500 pieces from his collection.

“Massive” and “enormous” are some words that come up when considering his taste, which runs to works like Per Kirkeby’s fortress-like sculpture Untitled (1994-2003). Van Caldenborgh has provided a unique home for artists who dream big. “It weighs five tons and I had never imagined it would find a home,” Antony Gormley told the New York Times of Still Leaping, for the park.

Christoph Buchel’s Unplugged (Simply Botiful) (2006-07), sponsored by Hauser & Wirth and Maccarone, in “Art Unlimited” at Art 38 Basel. Courtesy artnet Magazine.

Dimitris Daskalopoulos

Just take a gander at the website of the D.Daskalopoulos Collection, which declares prominently its jumbo-sized commitment to Big Art: “There is a high density representation of large-scale installations,” the site says, adding crucially, “the collection assumes the responsibility of the logistical and conservation commitment this requires.”

Among other feats, Daskalopoulos co-purchased Matthew Barney’s Chrysler Imperial (2002). Another massive work in the collection is Unplugged (Simply Botiful) (2007) by Christoph Büchel, which measures some 450 square meters.

Ugo Rondinone, Turn Back Time, Let’s Start This Day Again (2009). Courtesy Arsenal.

François Odermatt

The Montreal collector has become known for his taste for the monumental. He is a partner in Montreal’s Arsenal Contemporary Art, a private exhibition space thought to bring the “Miami model” of flashy private art showcases to Canada; at more than 7,400 square meters, it is described as “one of the only art spaces in Canada where you can drive a truck in from street level”—the better to show off his outsized tastes.

That’s the kind of venue that makes works like Ugo Rondinone’s life-sized casts of a 2,000-year-old tree make sense.

Helio Oiticica, Invenção da cor, Penetrável Magic Square # 5, De Luxe (1977). Courtesy Imhotim.

Bernardo Paz

“Brazil’s Inhotim park celebrates giant art amid nature,” the BBC reports, referring to the sprawling sculpture park the mining magnate has founded, proposing a new relationship between art and nature.

Among the many highlights are Helio Oiticica’s 1977 installation Invenção da cor, Penetrável Magic Square #5, De Luxe, a landmark architectural collection of freestanding, brightly colored walls. But Paz also has gathered works like Beam Drop, the remains of an epic 2008 performance by the late Chris Burden, where he dropped “locally sourced” I-beams from a crane into the ground to create a post-industrial Stonehenge.

Tom Friedman, Untitled (2003). Courtesy Warehouse Dallas.

Cindy and Howard Rachofsky

Dallas collectors Howard Rachofsky like flashy stuff, so naturally their tastes run large. Their mansion is built to feel like an art gallery, even featuring a Tiled Planes work by Robert Irwin right in their front yard.

The couple also founded, with Vernon Faulconer, the Warehouse, a 52,500-square-foot exhibition space—ample room to show off such brash Rachofsky trophies as Louise Bourgeois’s Cell (You Better Grow Up) or Tom Friedman’s Untitled (2003)—a towering, slouched blue figure carved from blue Styrofoam (the latter is literally a museum piece, being co-owned with the Dallas Museum of Art).

Random International’s Rain Room at the Yuz Museum. Courtesy Yuz Museum.

Budi Tek

The Chinese-Indonesian art heavyweight is at the top of the list of Spiegler’s list of collectors whose taste is driving the market for Big Art. His Yuz Museum in Shanghai is located in what was once the hangar of Longhua Airport; “By retaining the unique sense of grandeur of this enormous structure, the space perfectly sets off the magnificence of the installations in YUZ collection,” the space’s site boasts. Sometimes his taste is spectacularly classy—currently, he has on what is described as the “world’s largest Giacometti exhibition.” But sometimes, it is just spectacular: He commissioned a special showing of Random International’s blockbuster Rain Room installation, boasting that the Shanghai presentation had been scaled up by 50 percent.

Anish Kapoor, Dismemberment, Site 1 (2009). Courtesy Gibbs Farm.

Alan Gibbs

“Go big or go home is the sentiment at Gibbs Farm.” So says one description of the 1,000-acre art park on Kaipara Harbour founded by one of New Zealand’s biggest businessman, Alan Gibbs.

The offerings, indeed, are overwhelming, including Anish Kapoor’s giant, otherworldly Dismemberment, Site 1 (2009), which looks like an alien deposited a giant musical instrument into the landscape, and Richard Serra’s winding 252-meter-long Te Tuhirangi Contour (1999/2001).

Tomás Saraceno, Cloud Cities / Air-Port-City 4 Modules Meta (2010-2011). Courtesy Domaine du Muy.

Pierre Lorinet

The French-born Lorinet is the chief financial officer of Trafigura, one of the world’s largest commodities trading houses. For his 40th birthday, he decided to start collecting art in a big way, with advice from art advisor Edward Mitterrand.

Lorinet become a partner in Mitterrand’s Domaine du Muy, a 24-acre park outside of St Tropez, where he can show off acquisitions such as Tomas Saraceno’s Cloud Cities / Air-Port-City 4 Modules Metal (2010-2011), which, as Lorinet maintains, even a man of his considerable means would not have the space to show at home.

Huma Bhabha, The Orientalist (2007). Courtesy The Mallin Collection.

Sherry and Joel Mallin

The Mallin’s private estate in Pound Ridge, New York features not just the 15-acre Buckhorn Sculpture Park for their giant collection of 70 outdoor sculptures, but a 10,000-square-foot facility that they literally call the Art Barn. This gives them the room to show off works like Huma Bhabha’s The Orientalist (2007) a towering, weathered sculpture of a king on a throne, or Jeppe Hein’s Site Rotating Pavilion (2008), a mirrored labyrinth that the Danish artist describes as one of the most ambitious pieces he’s ever created.

“It was a very complex production,” Hein told W. “They had to build a huge foundation, excavate tons of earth, and a new road was needed for the big trucks.”

Jaume Plensa, Nomade (2007). Courtesy of Des Moines Art Center.

Mary and John Pappajohn

The Pappajohn Sculpture Park in Des Moines, completed in September 2009, is a testament to the giant-sized ambition of its namesake.

“When John Pappajohn calls you on the phone and says, ‘I have an idea,’ you know it’s something big,” Jeff Fleming, the head of the Des Moines Art Center, said on its opening of the collection, which boasts that it features art valued at $40 million. It offers such Brobdingnagian fare as a 1,000-pound Louise Bourgoise Spider as well as Jaume Plensa’s Nomade (2007)—a three-story-high silhouette of a man created using stainless steel words.

Interior of Ann Hamilton’s The Tower. Courtesy Oliver Ranch.

Steve and Nancy Oliver

Located on a 100-acre property north of San Francisco, the Oliver Ranch is a showcase for its namesake couple’s taste for ambitious, site-specific work, giving lots of room for artists such as Richard Serra, Robert Stackhouse, Ann Hamilton, Ursula Von Rydingsvard, and Miroslaw Balka to stretch their wings.

The centerpiece of their collection is Hamilton’s The Tower, the artist’s first permanent installation, which took three and a half years to complete; it’s a winding sculptural tower that can host up to 150 people in its “unique acoustic environment,” an artwork that is also designed to host a living program of performances.

Tony Oursler, Cognitive & Dissonance (2010–2013). Courtesy Ekebergparken.

Christian Ringnes

The Norwegian real estate millionaire has made a name for himself by backing Ekebergparken, a 62-acre sculpture park opened in 2013 owned by the city of Oslo, and studded with Ringnes’s personal treasures.

In this setting, there’s space enough to accommodate unconventional initiatives like Sarah Sze’s 22-foot-long Still life with a landscape (Model for a habitat), a sculptural bird feeder; Tony Oursler’s Cognitive & Dissonance, giant projections into the trees representing the chaos of the digital age; and even a 2013 performance by Marina Abramovic, for which she had 300 people screaming together in tribute to Edvard Munch’s The Scream.

Julius Popp’s Bit.Fall at the Museum of Old and New Art.

David Walsh

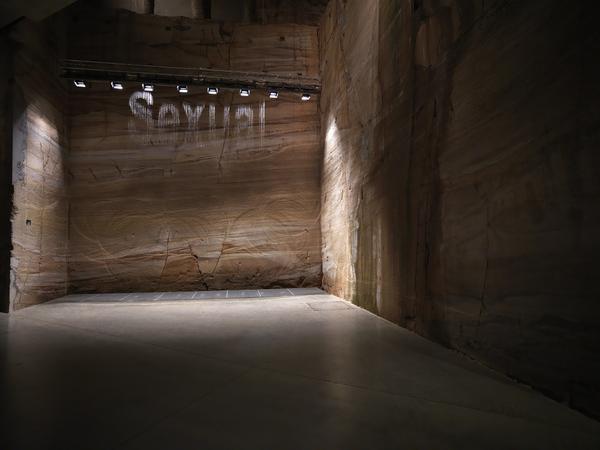

The Tazmanian gambling millionaire (not a casino millionaire, mind you, but a gambling millionaire) has become something of a legend for his risk-taking taste, creating his custom-museum, the Museum of Old and New Art, accessible by ferry from Hobart.

His tastes certainly vary—but he likes his art brash, which often means big. Visitors are greeted aboveground by a James Turrell skyspace, and a full-sized cement mixer made out of densely patterned, latticed metal by Wim Delvoye, before descending into the earth to see the treasures of the cave-like museum, which include Wilfredo Prieto’s full-sized Untitled (White Library) (2004 to 2006), an all-white ghostly simulation of a library, and Julius Popp’s towering Bit.Fall, a cavern-filling installation that squirts out random phrases culled from the internet in waterfall form.