Art World

How Edward Munch’s Pioneering Use of Color Science Put Art on the Road to Abstraction

The Norwegian was one of the first to apply color theory to art.

The Norwegian was one of the first to apply color theory to art.

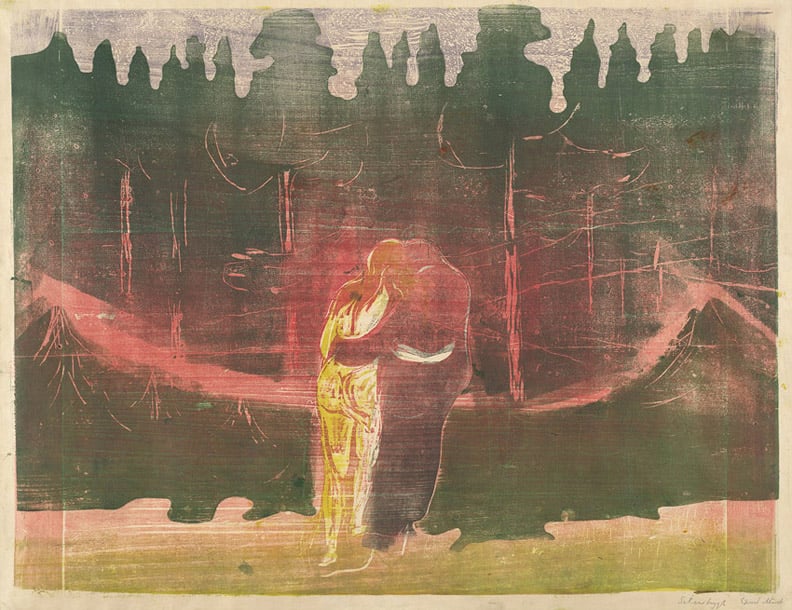

When people think of Edvard Munch’s contribution to art history, they typically look to the expressionistic imagery the moody Norwegian artist used to capture the perturbed psychology around the turn of the 20th century—the screaming figure on the boardwalk, for instance, or his pairs of ghoulish lovers. There is a case to be made, however, that Munch was equally pathbreaking in another less-remarked-upon aspect of his work: his use of color.

For Munch, color was not merely decoration. It was the arena in which the era’s novel scientific and philosophical concepts could be revealed, and exploited.

This fascinating subject is at the heart of an upcoming show at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, that will use 21 of the artist’s prints to highlight how Munch implemented color theory in his work based on new discoveries in physics and Theosophical thought that emerged in the second half of the 19th century.

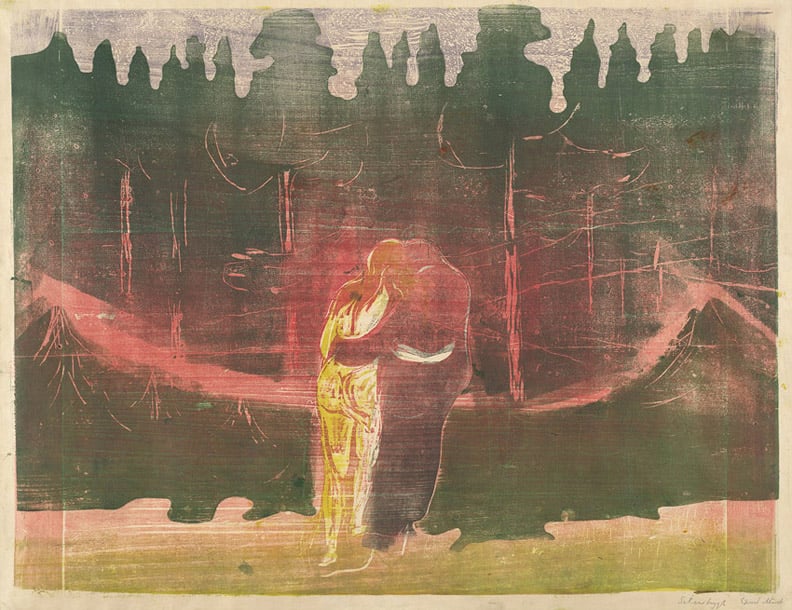

Edvard Munch Ashes I (1896). Photo: © Munch Museum/Munch Ellingsen Group/ARS, NY 2009.

Munch, it turns out, devoured popular manuals on the science behind color and the powerful visual and physical effects that color can have on us. Effectively, these writings purported that there are forces at work in the universe that impact the world around us but are imperceptible to the human eye—a notion that was very au currant at the time, given the great public excitement over such recent scientific breakthroughs as the discovery of x-rays, electricity, magnetism, and the beginnings of quantum mechanics.

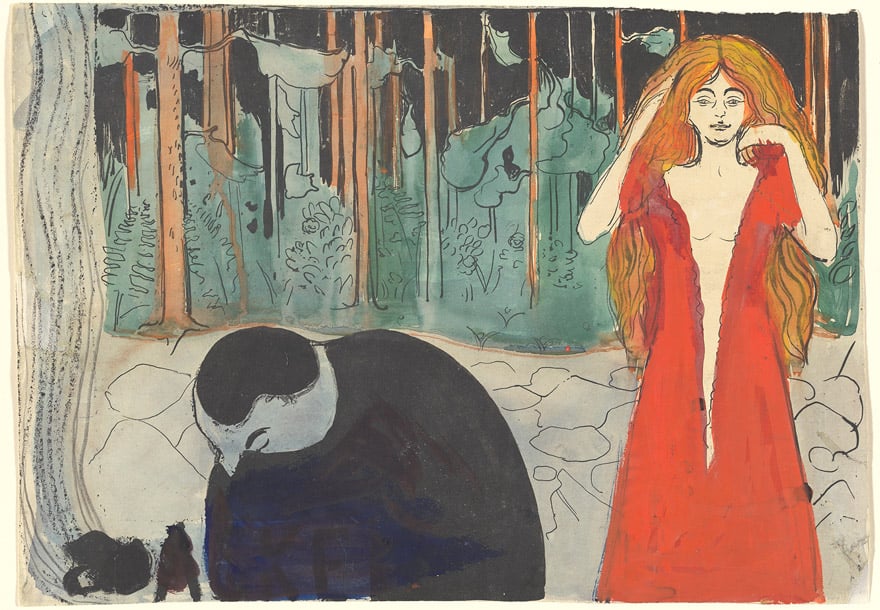

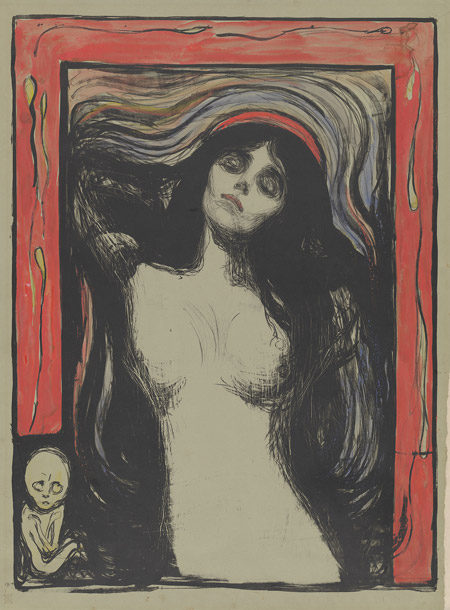

These discoveries included new insights by physicists revealing how humans interpret color. For example physicists discovered that, among the different photons that are present in visible light, the ones that have the longest wavelength look red to us, while the ones that have the shortest wavelength look blue to us; because red has a greater wavelength, it is interpreted faster by the human brain, and therefore appears more striking. Red, of course, becomes a key color for Munch, drawing the eye in many masterworks from Vampire (1895), where the woman’s long crimson tresses drape over her victim, to the blood-red sky of The Scream (1893).

The discoveries coincided with the advent of popular spiritual theories propounded by such Theosophists as Annie Besant and C.W. Leadbetter, whose influential book Thought Forms (1901) described individual colors as emitting different energies—ideas that “were current in literary and artistic circles that Munch was familiar with,” according to Jonathan Bober, curator of prints and drawings at the NGA.

The artist primarily applied these concepts to his work for theatrical effect, conveying the emotion of his subjects and eliciting an emotional reaction from the viewer in turn—aims that took precedent for Munch over accurately depicting the world around him, a radical approach in the conservative 19th-century art world.

Edvard Munch Madonna (1895/1896). © Munch Museum/Munch Ellingsen Group/ARS, NY 2009.

In contrast, the Norwegian’s contemporaries in France were working with less sophisticated color models. Artists such as Paul Gauguin, Maurice Denis, and Odilon Redon were all basing their choices on a “very subjective use of color which we usually just attribute to their personality and the start of Modernism,” the curator said.

According to Bober, Munch’s implementation of Theosophical and scientific color theory in art had a profound effect on subsequent generations of artists, influencing the bold colors of German Expressionism and the Viennese Secessionists, for example.

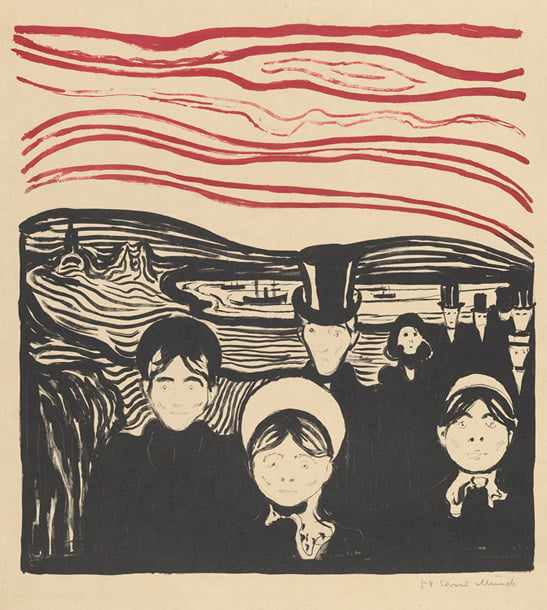

Edvard Munch Anxiety, 1896 (1896). Photo: Munch Museum/Munch Ellingsen Group/ARS, NY 2009.

“The whole complex of late 19th- and early 20th-century scientific and philosophical thinking certainly informs the overwhelming movement towards the non-representational at the very least,” Bober continued. “Quantum mechanics has been very well correlated with the emergence of non-representational art.”

While other artists were aware of those theories at the time, “it is with Munch that the correlation is closest and most easily and readily demonstrated,” Bober said.

Scholars like the University of Texas’s Linda Henderson later suggested that the act of looking beyond surfaces, and recognizing the underlying instability of the world around us, greatly influenced artistic production at the turn of the 19th century and eventually lead to the birth of abstraction, particularly Cubism.