Art World

Why Collaborative Curating Makes Sense for a Divided Political Era

Amanda Hunt and Eric Crosby, curators of the Carnegie's "20/20," talk about an unusual partnership of institutions and ideas.

Amanda Hunt and Eric Crosby, curators of the Carnegie's "20/20," talk about an unusual partnership of institutions and ideas.

In the wake of election of Donald Trump, artists and curators have been wrestling with the idea of how to respond creatively, through their practice, to the current charged political climate. Such is the challenge that curators Amanda Hunt and Eric Crosby have explicitly given themselves with their exhibition “20/20,” which opens this week at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh. During what its press release calls “a tumultuous and deeply divided moment in our nation’s history,” “20/20” promises to make the case for art’s role in tackling the complexities of US history.

Moreover, it promises to do so in the form of a dialogue. Hunt, formerly an associate curator at the Studio Museum in Harlem, currently serves as director of public programs and education at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. Crosby is the curator of modern and contemporary art at the Carnegie. The two worked in tandem to present a show that brings together the collections of the Studio Museum and the Carnegie, focusing on the works of 20 artists from each institution to tell a larger story.

The show is subdivided into sections ranging from “The American Landscape” to “Forms of Resistance.” Its curatorial rumination on the cultural fabric of the US proceeds via the works of figures including Lyle Ashton Harris, Jasper Johns, Jon Kessler, Nari Ward, David Hammons, and James VanDerZee.

Recently artnet News sat down with both curators in Pittsburgh to discuss the exhibition, their collaboration, and what they believe the responsibility museums should have to their community.

How did this collaboration, this exhibition, come together? What was the genesis for this project?

Eric Crosby: We talk about the exhibition as offering a metaphoric view of America today through the dialogue created between the works on display. Some themes became very apparent, and cohered around specific artworks.

So the first work you see in the exhibition is the Carnegie Museum’s painting by Horace Pippin, Abe Lincoln’s First Book (1944), in which the artist depicts a portrait of Abe Lincoln at night as a young man, lying under his bear skin rug, in this very dark cabin, reaching out by candlelight for his first book.

Horace Pippin, Abe Lincoln’s First Book (1944). Image courtesy Carnegie Museum of Art.

Amanda Hunt: It made us cry in the galleries.

EC: This is a moment, in the midst of our collaboration where you say, “Oh, I get it now. Thank you Horace Pippin!” The ideas expressed in this 1944 image felt relevant today. For us as citizens, as curators, seeking knowledge and understanding—even when it appears that there is kind of a darkness around us—is a really vital aspect of the work. That became a real genesis for the project, and for the thematic narrative of the exhibition.

When did you have that moment of realization?

AH: It was about six months ago. I came for a site visit, and it was just perfect. Eric said to me, “I just want to show you something that hangs in our permanent gallery all the time.” And it was just like, “Are you kidding me?” First of all, I’ve always wanted to do an exhibit of Horace Pippin’s work—I grew up in Philadelphia.

We just walked in front of [the painting], and we thought, “This is it. We start here.” And it really does just encapsulate our values, and everything that we are trying to say.

“A More Perfect Union” is the theme of the first gallery, which begins with the Horace Pippin painting. This section is also framed by Jasper Johns’s Double Flag (1962–1999) and Lyle Ashton Harris’s Miss America (1987–88), which represents a queering of the flag, wearing it a bit differently in terms of its identity.

Lyle Ashton Harris, Miss America (1987–88). Image courtesy The Studio Museum in Harlem. Photo: Sasha J. Mendez

This room looks at the democratic principles of the country. Installing this show the day after July 4th… A lot of this has been kismet. Finding the Pippin, installing the show on the day after we celebrate a country that a lot of people have ambivalence about right now—in my social media feed at least! We’re not taking the moment lightly.

The show is meant to be fluid. Yes, there are distinctive sections, but it’s meant to all work together. You can move back and forth. It doesn’t matter where you start, [the artworks] will be speaking to each other between walls and galleries.

Many of our section titles refer to works in the space of that section of the show too. So the “Working Thought” section refers to Melvin Edwards’s “Lynch Fragments” series, and really deals with economy, labor, how this country was built: who built it, without credit or pay, for hundreds of years.

This history [of racism] is probably still with us today, with the prison industrial complex, of course, as Titus Kaphar’s works get into. But we also tackle the classic history, via Kara Walker’s vignette from a larger series of prints that the Carnegie has in its collection; Noah Davis’s Black Wall Street, which touches on a larger black narrative, of a prosperous black community that was destroyed. That’s a heavy gallery.

Can you talk briefly about the process of working closely with these impressive collections in dialogue with each other?

EC: As curators who are looking after and working with collections, we started asking ourselves: In what way can we work to be responsible with those collections and to reflect our national conversation, our state of affairs? As a curator, you have a collection—only a fraction of which is shown at any given time—you have words, you have visual space that you can fill with artwork, you have an audience. Those are the raw materials. What’s really interesting, though, is when there can be a conversation as well.

This show felt like a really great opportunity for us, as two curators who wanted to work together, two institutions, two cities—with these particular audiences and these particular artists, some of whom overlap between collections and some of whom have very distinct histories within their collections.

AH: The collections are important, but so too is being able to foreground some of our political leanings or perspectives within the context of an exhibition. You know, there was a point where I marched for Trayvon Martin and Mike Brown, and I just couldn’t be angry anymore. I couldn’t figure out what I could do to start affecting change, either in a more immediate sense or in a collective community sense. So this show represents our power, our purview—this is what we know and have been trained to do, and have voice and ownership of, and a platform for. We’re curators at major institutions in America. And that’s powerful.

EC: This is also a time when people are asking more and more of their museums. There’s the need to be marching and having a voice outside of your professional life—but there’s also the question of what people are asking of museums, and what you’re asking of yourself.

The exhibition was in the works before Trump became president. Obviously, things have changed tremendously since then. Prior to the election, how was the show conceived?

AH: It was a little more loosely defined. We came up with a title very quickly—having fun. We do that. “20/20” was initially like “Hindsight 20/20,” because Eric had already come to see a bunch of my shows at the Studio Museum [when I was still working there], and really liked them, thematically. So that was where the conversation began. We were looking toward—but not forward to—a post-Obama moment, and wanting to reflect a little bit, personally, politically, artistically, and curatorially on the subject. And then, of course, everything changed with this new administration. It changed the tone and urgency.

There is great sense of urgency right now, in terms of what responsibilities museums have to their surrounding communities. As curators, in response to the current administration, how do you navigate that space in terms of working outside the museum walls and involving the local community, with this show in particular?

EC: Well, for us it’s been through partnerships, especially with other organizations in Pittsburgh, mapping out a programming strategy over the run of the exhibition that emphasizes those partnerships. For one, we’re working with City of Asylum, a Pittsburgh-based organization that gives political asylum to writers from around the world who are being persecuted. It allows them to create a life for themselves in Pittsburgh, or elsewhere, if they choose to leave. City for Asylum has become a really important center for bringing together artistic and marginalized voices that need support. We’ve been working with them to commission writers to write responses to the exhibition, whose work will appear in the museum and in public meetings.

Another group we’ve been working with is By Any Means which is run by Kilolo Luckett [former director of development at the Andy Warhol Museum]. The mission of her non-profit is really to convene a conversation, in Pittsburgh, that advances interest in black arts in the city, and brings black voices from outside [the art world] into the conversation. We’ve asked Kilolo and her group to help us conceive of a series of “in-gallery” conversations throughout the exhibition, bringing in community stakeholders from artists and art historians, to gallery monitors, gallery guards, and teenagers.

Noah Davis, Black Wall Street (2008). Image courtesy of The Studio Museum in Harlem. Photo: Adam Reich.

AH: The first day of the exhibition will be open to the community and we hope to encourage engagement across age groups and communities. There will be art-making activities, music, and a pretty great panel discussion between myself, Eric, Abigail Deville, Kori Newkirk, and Jon Kessler, who are featured in the exhibition in the “American Landscape” section.

For me, curating has always been about educating others, but not in a didactic way. I will talk to anyone! Coming from the Studio Museum in Harlem, and being rooted in that community, I took the educational aspect very seriously, and produced works in public parks to honor that impulse in a more public-facing way.

Now, as director of education at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles (MOCA), I firmly believe in that opportunity, in that space—that’s my job.

One of more remarkable aspect of the exhibition is the presentation of photographs by James VanDerZee and Teenie Harris together in one room. I wasn’t familiar with Harris’s works, but the correlations between the artists is astounding.

EC: That gallery is really an exhibition inside of the exhibition, something that we just really had to do, which is to bring together these two iconic photographers who are associated with our respective museums. I don’t think it’s really been done before. They are footnotes in each others’ histories, but they’ve never been brought within an exhibition space together.

Teenie Harris documented life in the city of Pittsburgh over decades. And just as a side note, the amount of work [at the Carnegie] that goes on in terms of maintaining this archive, identifying the people in these photographs, the locations of all these images, and stitching together these stories using oral history—it’s remarkable.

In this section of the exhibition we’re really focusing on bringing together the idea of VanDerZee as a largely studio or interior photographer—he was out on the street too, but we wanted to capture that aspect of his craft—and then juxtaposing it to the other side, with Teenie: “Teenie on the beat” as a newspaper man, recording the comings and goings of the city.

From my perspective, works from the Carnegie collection can take on a more political valence through this kind of dialogue. For instance, just think about where the Horace Pippin usually hangs—near Edward Hopper. In that context the work is about the history of painting, rather than a conversation about politics and identity.

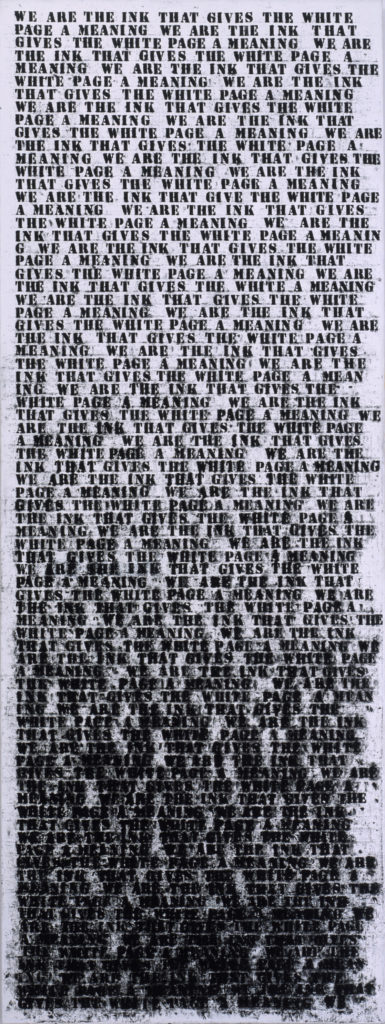

Finding ways to reframe and recontextualize the conversation is always incredibly valuable. You learn so much about works when you put them in a new light. Just bringing the [Glenn] Ligon next to the [Jasper] Johns print, you see the Ligon totally differently! I understand his text in a completely different way.

Glenn Ligon, Prisoner of Love #1 (Second Version), (1992). Image courtesy Carnegie Museum of Art. © Glenn Ligon.

Can you describe what it’s like to collaborate with each other?

AH: I think I can say that both of us work really intuitively, and that this process has been intuitive. We don’t argue a lot. I think we make cases or defenses for certain decisions—but it’s fun, and it’s a great intellectual exercise. We get what the other is doing, and we respect it, and it’s been a really fluid collaboration in that way.

EC: That’s rare in the art world, don’t you think?

AH: Authentic collaboration? Yes, I think so, absolutely.

Thomas Lax, who is now at MoMA and is a dear friend and trusted colleague—I remember him asking the question, “Why isn’t this built into the field? To support each other? And to have a place for feedback?”

You work so hard to mount the exhibition, and then it’s up, and you receive public critical reception, either from reviews or just from conversations at openings. But what about your peers and colleagues? Thomas did that for me, and I did that for him. And Eric and I are doing that very actively in this exhibition. I do think it’s quite rare.

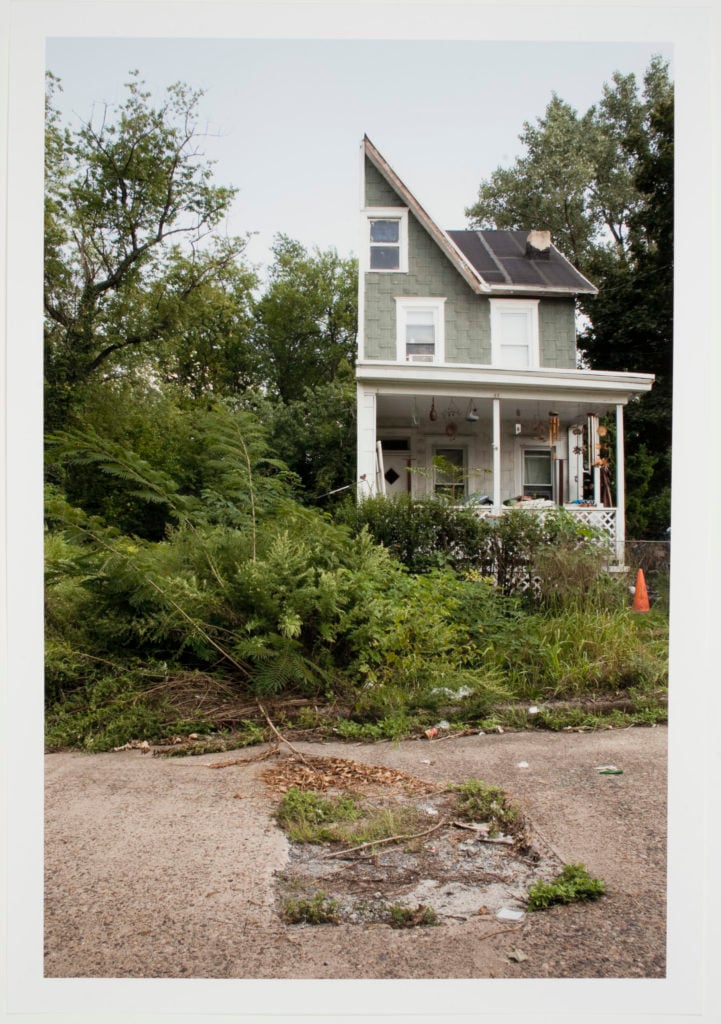

Zoe Strauss, Half House, Camden, NJ (2008). Image courtesy Carnegie Museum of Art. © Zoe Strauss, By permission of the artist.

In some sense, this exhibition is a reaction to a political climate. But from what I’ve seen there doesn’t seem to be a strong political message, or there are no polemics. Would you say that the show offers an opportunity to ruminate on the current state of our country?

EC: Here’s the thing: We’re in a time where people think political means partisan. But art can have a very different conversation than that.

I think that art actually helps clear a path for a broader mode of thinking about what is political, and how we understand it as citizens, as a population, and as patrons of museums whose collections are supposed to reflect us. And I think that’s what our show does, and what more shows should try to do. When I hear, “Is the show political?”, I hear in my mind, “Is it partisan?” I want to stop jumping to that conclusion, because I don’t think that’s what we should be talking about.

AH: We will clearly need to make that distinction. Art will not solve anything. There have to be multiple strategies. But Horace Pippin’s work, made in 1944, did something in 2017 that was a catalyst for this exhibition, and it’s really powerful. Let’s not forget that. That’s the power of art.

This show is set against a backdrop that is changing constantly. You know, with a president who is always tweeting, with the environment of breaking news—we can never be that responsive. But what we can do is help to carve out a different space. And that is very much what this show stands for.

Thaddeus G. Mosley, Georgia Gate (1975). Image courtesy the Carnegie Museum of Art.

It’s not just a space to distract yourself from what’s happening.

AH: Exactly.

EC: Or to be totally reactive.

It doesn’t feel reactive. It could have been way more “partisan,” as you put it, or very lefty, but it doesn’t come across that way at all. It’s a pleasant space to be in.

EC: We did want it to be a space that was welcoming to everyone, a space in which to reflect. The positions are largely the artists’ positions, not our own.

AH: We don’t want to make it a polarizing experience. It’s a democratic experience. There are so many perspectives and realities in our country, so we’re not trying to assume anything either. We know, privately, our positions. People will come in with their assumptions, and I hope that through the works in the show, they will have to confront those or shift those, or just find empathy in certain works, or just a resonance that feels right at this moment.

All of that opportunity is present in the exhibition. We didn’t want to close anything down, or create a situation where it was like, “Your politics are wrong—ours are right!” You are entering our space, and all are welcome.

“20/20” is on view at the Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, July 22–December 31, 2017.